Design School Faculty Member Xiangnan Xiong Weighs in on the Debate on Architecture that Aims to Be High and Low Brow at Once:A Summary of the Article “Double-coding in Effect: the Reception of the Piazza d’Italia”

Xiangnan Xiong

Faculty member Xiangnan Xiong published her research in the Journal of Architecture, volume 29. The Journal of Architecture is a core journal of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). Part of the article had been presented at the 76th Annual International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, which took place in Montréal and virtually in 2023.

How are post-modern sites received? To answer this, Xiong’s “Double-coding in Effect” investigates the iconic post-modern site Piazza d’Italia, focusing on its mixed reception. Central to this investigation is an appraisal of double-coding, a seminal concept that has shaped post-modern architectural theory and practice.

1. Charles Moore, St Joseph’s Fountain, Piazza d’Italia, New Orleans, 1978 (author’s photo)

Double-coding is an approach that seeks to communicate with two audiences—the general public and architectural professionals—through a building language that blends modern elements with other forms (including historical, vernacular, and commercial). Piazza d’Italia, designed by American architect Charles Moore, is often seen as a prime example of this theory (fig.1). The site features five Classical orders and diverse motifs from a variety of sources. As Moore envisioned, the design would speak to various audiences: the Italian community would appreciate the references to archetypal piazzas, fountains, and classical orders; the colourful décor and neon lightning would attract fun-loving locals; the echoes of Hadrian’s villa and Schinkel’s triumphal gateways would not be lost on architecture professionals; and finally, as a whole, the picturesque layout and dynamic waterplay would create a sensuous and pleasant experience for all.

Yet, the Piazza d’Italia sparked controversy upon its completion in 1978. Local responses were mixed, and nationwide debates about the site continued into the early 1980s. These discussions allow us to understand the various perspectives one brings when experiencing a site. In turn, they offer a testing ground for us to assess how well double-coded schemes communicate with different audiences.

The elective nature of the site was a provocative topic. For some, the site’s individualistic design was delightful and entertaining, while for others, frivolous and gaudy. Supporters celebrated Moore’s audacious and inclusive approach while opponents claimed such the site’s bold composition presented “extremely poor taste” (fig. 2).

The usefulness of cultural references is questioned. Some found them irrelevant and patronizing on the grounds that the charm of the site lay more in its open plan and well-orchestrated forms than in its cultural allusions. Others, however, highlighted the key role cultural symbols play in creating a sense of place for the site. They noted further that one not need understand all the references to enjoy the site, but that such cultural imagery would greatly expand and enliven one’s visit.

The issue of architecture’s social commitment is also at stake. Some criticized that the site’s overly entertaining aesthetic undermined architecture’s political obligations and contributed to its growing social disengagement. Nevertheless, defenders of the site countered that social responsibility does not necessarily exclude pleasure and fantasy. The topic of ethnic design surfaced in the debate. Some reasoned that Moore’s efforts to evoke ethic identity were prone to misinterpretation and doomed to fail, for the essence of ethnic identity relies rarely on physical forms.

Local responses were no less divided. Some found the site fantastic and spirit-lifting while others saw it as distasteful and annoying. The use of commercial ornaments triggered the most debate. Supporters acclaimed them to be occasion-appropriate and site-specific, claiming that the intentional vulgarity makes the site all the more suitable for New Orleans, a city known for its quirky charm. However, for others, the use of vulgarity and popular motifs at a memorial site was a highly questionable act, making the site “outlandish” and “an eyesore.”

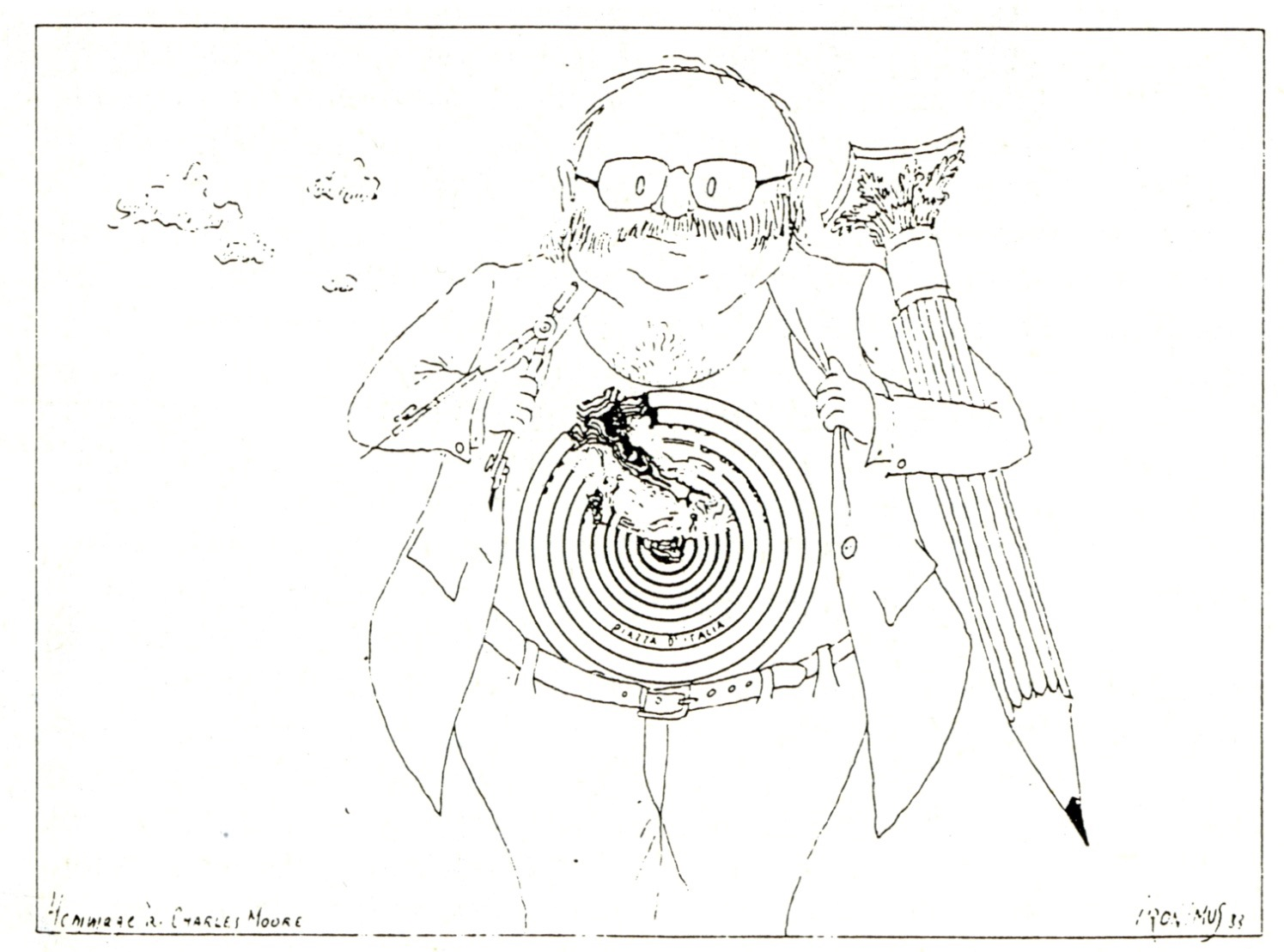

3. A cartoon by Gustav Peichl, published in Deutsche Bauzeitung 6(1989),89.

It turns out, however, responses from the public and professionals converged to a large extent. Despite nuances in perspective, both groups shared the same concerns and divided opinions. Concerning the formal composition of the site, views from the public and professionals were equally divisive. Reactions generally fell into two camps: those in favor of Moore’s whimsical design and those opposed to it (fig. 3). Yet, notably, members of both groups are found in both camps, suggesting that differences in views do not align to whether or not one is an architectural professional. This casts the usefulness of the double-coding’s divisive approach into question, and challenges post-modern discourse that relies on this very schism.