Academic News: Improving Healthcare Accessibility in Shanghai by Visualizing Disparity

Recently, Professor Chen Ruishan's team from the Department of Landscape Architecture at the School of Design in Shanghai Jiao Tong University published an academic paper titled "Spatial and Social Inequality of Hierarchical Healthcare Accessibility in Urban System: a case study in Shanghai, China." The paper was published in Sustainable Cities and Society, which is rated as having an impact factor of 11.7 and is assessed as a top journal by the China Academy of Sciences.

Introduction

Cities face four main challenges described below in quantifying spatial and social inequality in healthcare facility accessibility. These can help inform more actionable measurements that can help improve the equity in healthcare distribution.

Firstly, there is a lack of fine scale empirical data;

Second, there is a lack of comparative analysis of inequality in accessibility to different levels of healthcare facilities;

Third, there is a lack of comparative analysis of inequality in accessibility at multiple spatial scales;

And finally, there is a lack of analysis of disparities in accessibility by population subgroups characterized by demographical and socioeconomic status.

This research endeavors to bridge existing gaps in scholarly work by delineating the spatial distribution and hierarchical structure of healthcare accessibility at various administrative tiers in Shanghai, utilizing Web API.

This study aims to address three main research questions: 1) What are the spatial distribution characteristics of accessibility to all levels and overall hierarchical healthcare in Shanghai? 2) What are the characteristics of inequality of healthcare accessibility at multiple spatial scales, and 3) How does healthcare accessibility associate with social inequalities between groups with different socioeconomic and demographic characteristics?

Abstract

Urbanization is intensifying in cities, accompanied by burgeoning inequalities, notably in the healthcare sector. There is limited available research that offers a granular examination of healthcare resource accessibility across diverse population groups. In this study, we employ census data from all 6164 communities in Shanghai to investigate the relationship between multi-scalar spatial dimensions and the socio-economic (dis)advantage of populations concerning healthcare resource accessibility. Distinct from previous studies, this research quantifies social inequality by considering the demographics of community residents and their interactions with healthcare facilities. We elucidate the stratified spatial distribution of healthcare accessibility across various spatial scales in Shanghai, leveraging Web Application Programming Interface (API) technology and examine pervasive social inequalities across sub-district, district, and central urban-suburban divides, focusing on specific population subgroups including gender, age, education level, wealth, household registration, ethnicity, occupation, and housing living facilities.

Findings reveal that disparities in healthcare accessibility correlate with the quality of healthcare facilities, the socio-spatial attributes of localities, and the socio-economic and demographic profiles of the populations. The insights from this research will aid policymakers in enhancing the distribution and provision of healthcare resources, thereby promoting spatial and social equity in public healthcare system planning and implementation.

Healthcare accessibility inequality is linked to facility quality and locality.

Less urbanized areas show greater healthcare accessibility disparity.

Poor infrastructure and social marginalization worsen accessibility.

The implication is healthcare configurations should match disease patterns and demand.

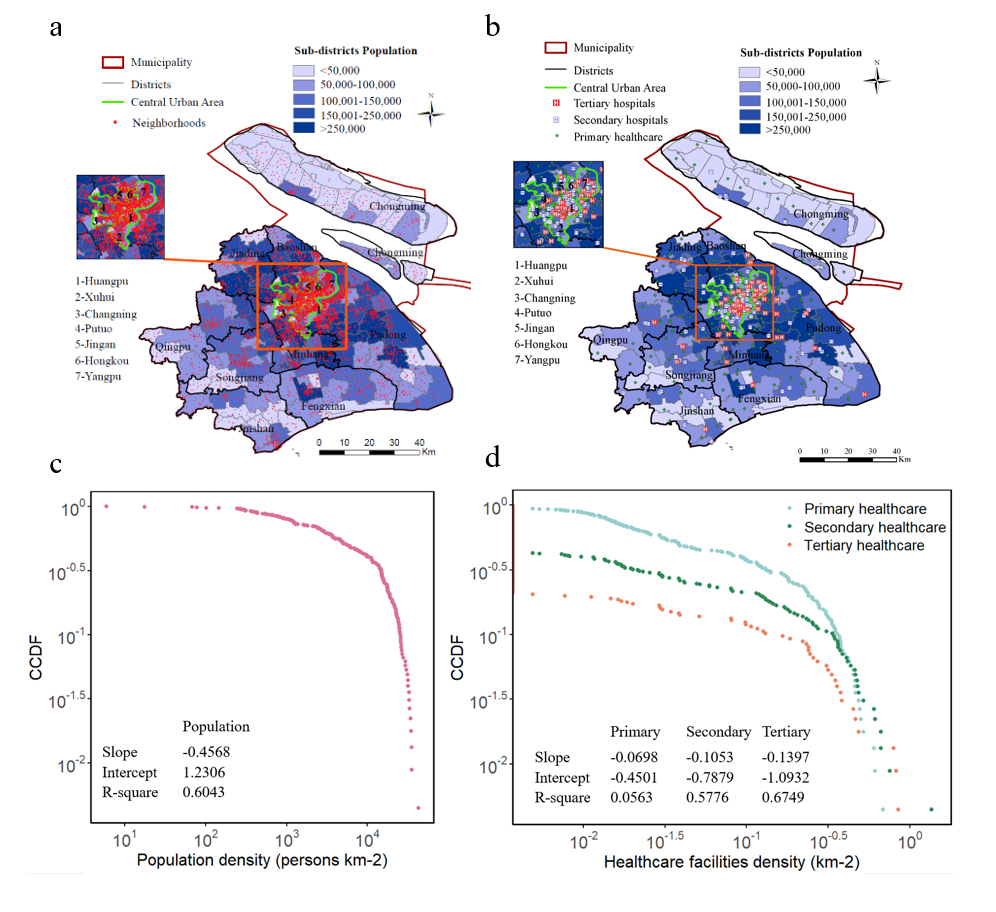

Fig. 1. Patterns of the existing population and facility distributions. a. Spatial distribution of population. b. Spatial distribution of hierarchical healthcare facilities in Shanghai. c. CCDF of population density at the sub-district scale. d. CCDF of hierarchical healthcare facilities density at the sub-district scale. The numerical values of the slopes, intercept and r-square of CCDFs using a linear formula are shown in the figures.

Fig. 2. Spatial accessibility to primary (a), secondary (b), tertiary (c) healthcare and general accessibility (d) to hierarchical healthcare at the community scale in Shanghai (Inverse distance weight interpolation analysis).

Fig. 3. Spatial pattern of Gini coefficient of accessibility to primary (a), secondary (b), tertiary (c) and general (d) healthcare at the sub-district scale.

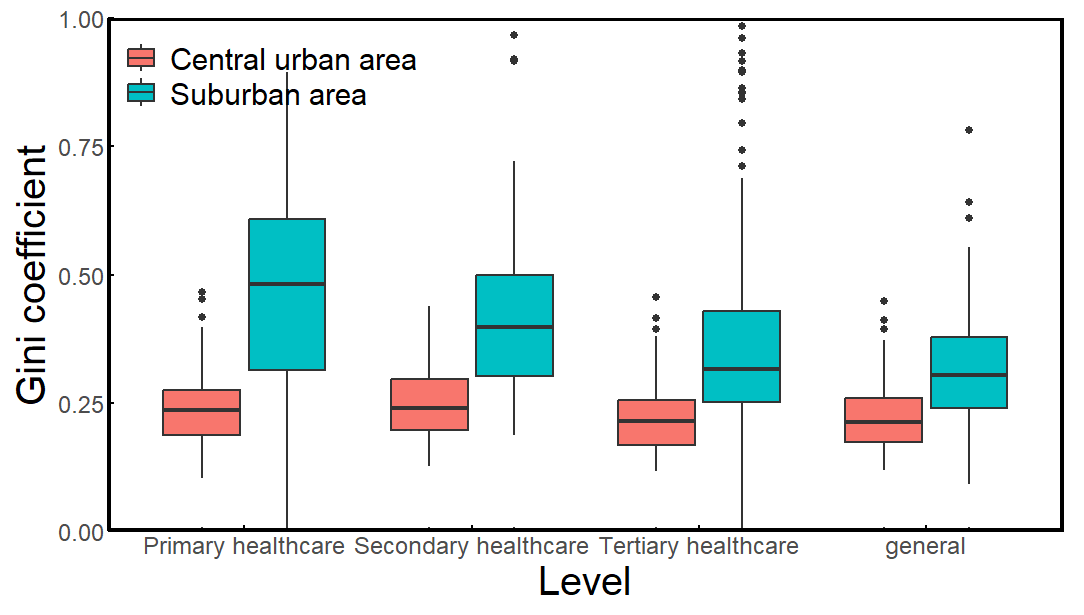

Fig. 4. Spatial inequality across central urban-suburban spectrum. Median across all points of analysis within a class is shown by a horizontal black line, with the 25th to 75th percentiles indicated by the box. Inequality comparisons between the central urban and suburban areas are statistically significant at p < 0.05 using student's t-test.

Fig. 5. Spatial inequality in accessibility to healthcare at the district scale. a. The Lorenz curve in accessibility to primary healthcare. Horizontal axis: cumulative share of population at the community scale. Vertical axis: cumulative share of accessibility corresponding to the proportion of population. b. The Lorenz curve in accessibility to secondary healthcare. c. The Lorenz curve in accessibility to tertiary healthcare. d. Gini coefficient of accessibility to hierarchical healthcare of 16 districts in Shanghai.

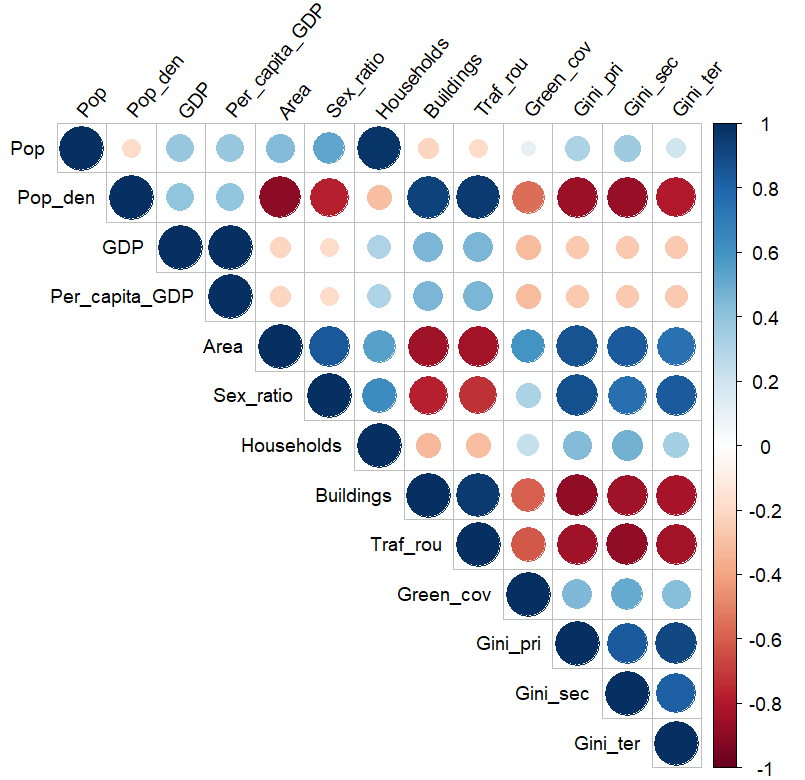

Fig. 6. Spearman's rank correlation matrix plot showing the relationship between a) Population (person); b) Population density (person km−2); 3) Gross Domestic Production (GDP, yuan year−1); 4) Per capita GDP (yuan year−1); 5) District area (km2); 6) Sex ratio of population (male/female); 7) Households; 8) Buildings (%); 9) Traffic routes (%); 10) Green coverage (%); 11) Gini coefficient of primary healthcare; 12) Gini coefficient of secondary healthcare; 13) Gini coefficient of tertiary healthcare. Correlations from negative to positive are indicated in red to blue respectively. The strength of the correlation is indicated by dot size and color saturation. Note that only significant correlations are shown (p < 0.05).

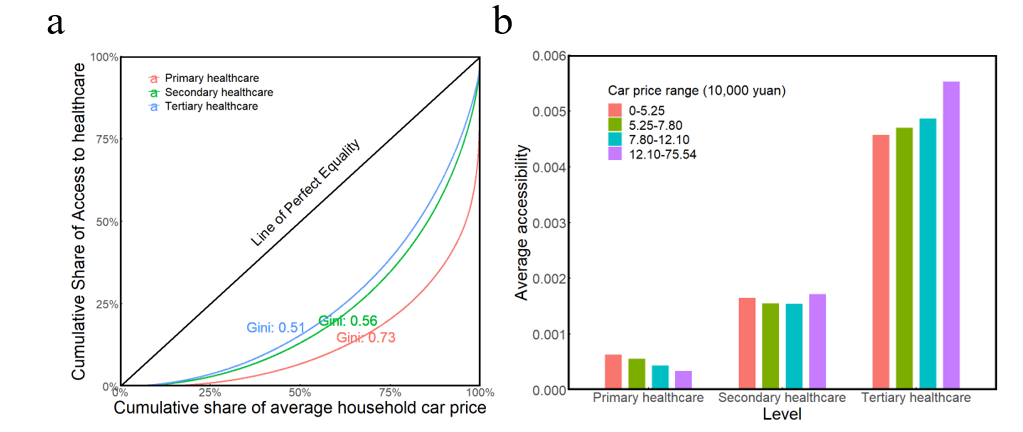

Fig. 7. Inequality among different wealth level communities. a. Lorenz curve and Gini coefficient of accessibility to healthcare among communities. b. average accessibility to hierarchical healthcare classified by average household car price. The legend bars are categorized according to the quartile of the average household car price.

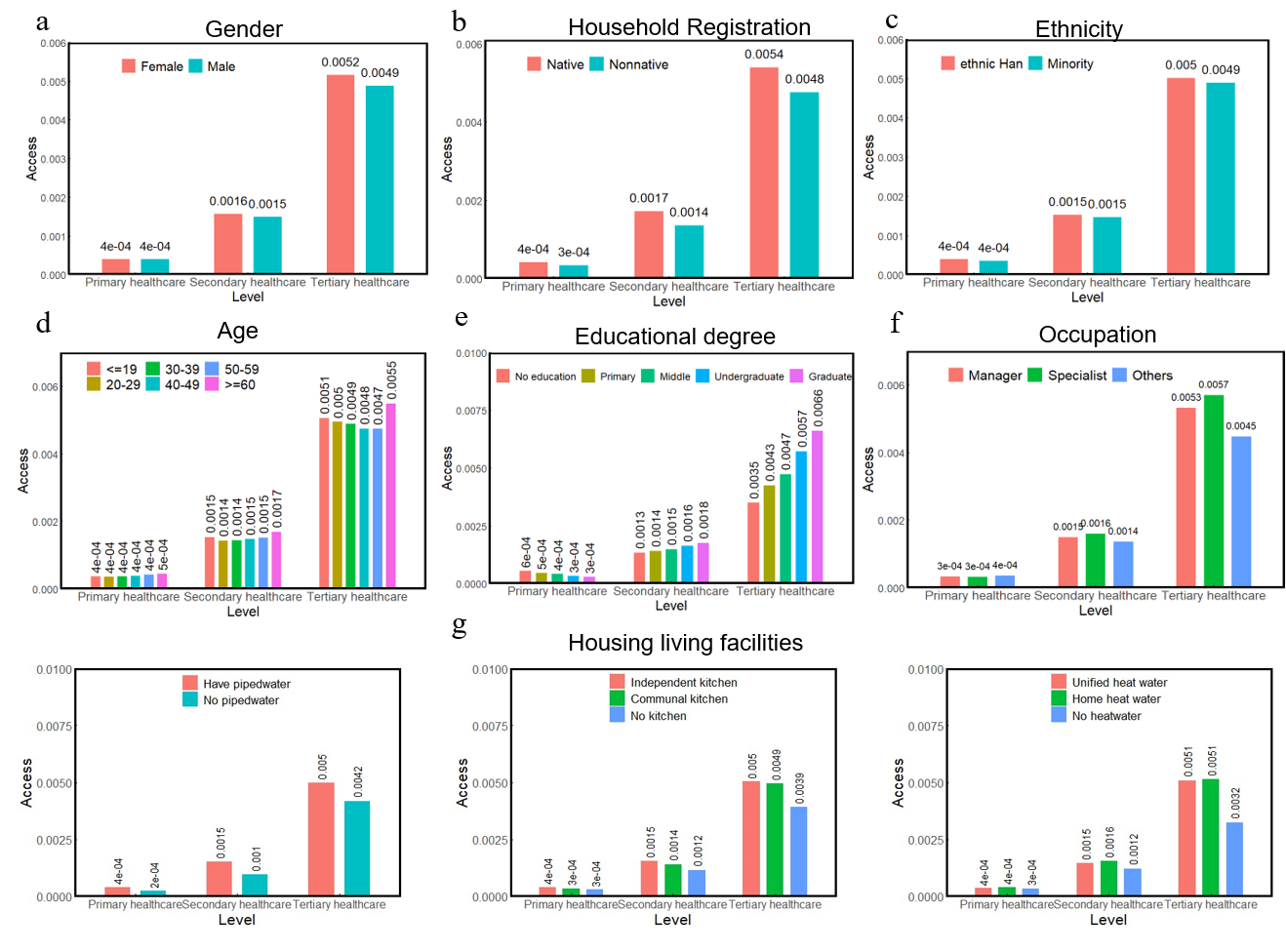

Fig. 8. Socioeconomic disparities in accessibility to hierarchical healthcare resources. a. The gender gap between females and males. b. Differences between subgroups registered in (native) and out of (nonnative) shanghai in terms of household registration. c. Differences between Han and minority nationalities. d. Age differences in access to healthcare. e. Differences among subgroups with different levels of education. f. Differences among different occupations. g. Differences among subgroups with different housing living facilities: piped water (left), kitchen (middle) and heat water (right).

Su Rongfei, a master's student of landscape architecture at the School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, is the first author of the paper. The corresponding author is Professor Chen Ruishan of the School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. The co-authors of the paper are Huang Xiao, an assistant professor of the Department of Environmental Sciences at Emory University, and Guo Xiaona, an assistant researcher at the School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Citation format:

Su, R., Huang X., Chen R., Guo X. (2024). Spatial and Social Inequality of Hierarchical Healthcare Accessibility in Urban System: a case study in Shanghai, China. Sustainable Cities and Society, (109), 105540.