Sheldon H. Solow Professor in the History of Architecture, The Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

Jean-Louis Cohen is a French architect and architectural historian specializing in modern architecture and city planning. His research has focused on architecture and urban planning in twentieth-century France, Germany, Italy, Russia and the United States; patterns of internationalization and regional cultures; the modernization of urban form in Paris; and city planning in colonial Algeria and Morocco. He has curated numerous exhibitions for the Pompidou Centre, the Pavillon de l’Arsenal, the Canadian Centre for Architecture, the French Institute of Architecture, the Museum of Modern Art and more. Research pursued on the field, at the contact of buildings, cities, and protagonists, as well as in the archives, has also led him to meet programs of historic preservation at the scale of the edifice or of entire cities, and to work as a consultant for NGOs engaged on this front, as well as with UNESCO, in Russia, France, and Morocco.

As an expert of the Creative City Network of Shanghai Think Tank, Jean-Louis Cohen was invited to attend the World Design Cities Conference on 16 September and presented a keynote speech on Design and the City.

Design and the City

(The text is organized by Xiong Xiangnan, Assistant Prof. of Architecture, Shanghai Jiao Tong School of Design)

Keywords

Design and City, Metropolis, Ecosystem for design, London, Berlin, Milan, Los Angles, Shanghai

Hello, I am Jean-Louis Cohen, architect, historian, curator. I'm talking to you from New York and I want to address an important issue, for Shanghai and the world altogether—the question of how cities and design operate together.

Shanghai is today one of the world's largest and most powerful metropolises, one which is extremely engaged in industry business and culture. And the question of business is sole by the competent authorities, and that won't discuss it today. But I want to focus on the question of our culture, of visual culture, art, creativity, trying to give a background to be kind of reflection you can have in Shanghai and to which I might participate one day. But major question is to know what makes a city creative and productive in terms of design understood at large from the design of buildings and maybe of landscape to a design of objects. I’m speaking to you not as a politician or as an entrepreneur, and not even as a designer, although I have a background in design, but as a historian and critic.

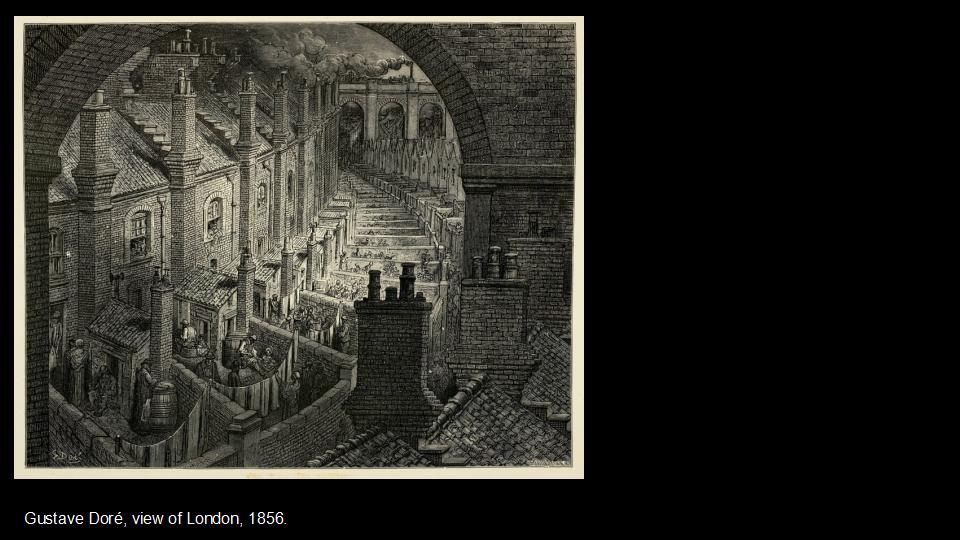

The first point I want to make brings us back to with the first city in history which was called a metropolis: London in the age of the Industrial Revolution. And I want to relate London and other cities to major stages in the development of design as a concern, as a discipline, and sometimes as a profession at the intersection between culture and production within visual culture production and also the modernization as a process at large, implying the transformation of the everyday, the transformation of the basic technologies of life and also, of course, the transformation of industry. Design as to concern and as a practice has not been born in the country. It is an urban phenomenon. Although of course, there is a long tradition of creativity in the shaping of everyday objects in the country and this is true for Europe, for the Americas, for China and has been documented by anthropologists and historians of material culture.

But as we understand design, which is the definition of an object to be produced industrially. It is clearly an urban, even I would say, a metropolitan concern. Design is not born in small cities or if the cities are small, they are always related to larger metropolises.

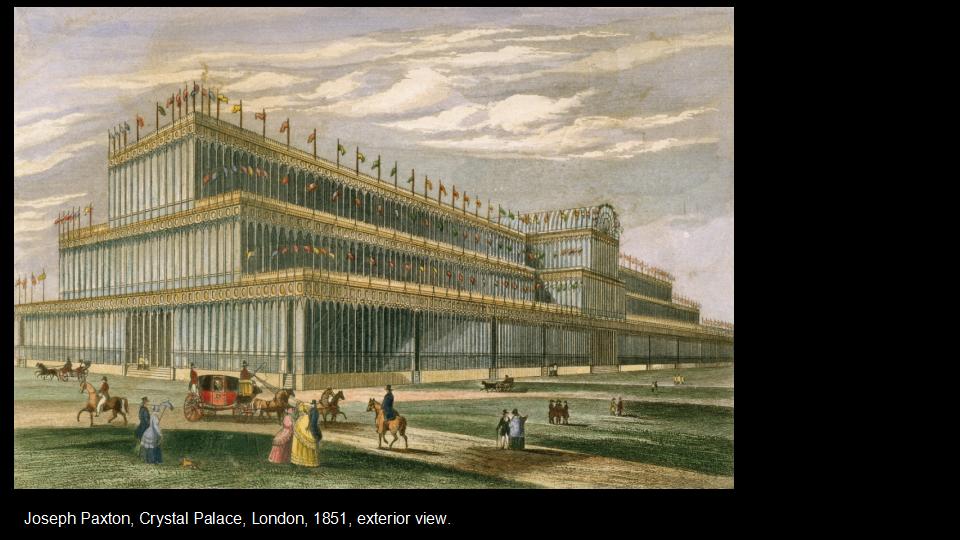

So in the case of London, the origin of the concern for design goes back to the world's first universal exhibition, held in 1851 in Hyde Park and marked, of course, by the erection of the extraordinary Crystal Palace, which was in itself a condensation of the Industrial Revolution. The building was meant for the display of industrial objects. But, it was itself built by industrial methods by Joseph Paxton, who was a gardener, with the use of prefabricated metallic structure of modular glass panes. The critical part for us was an industrial product.

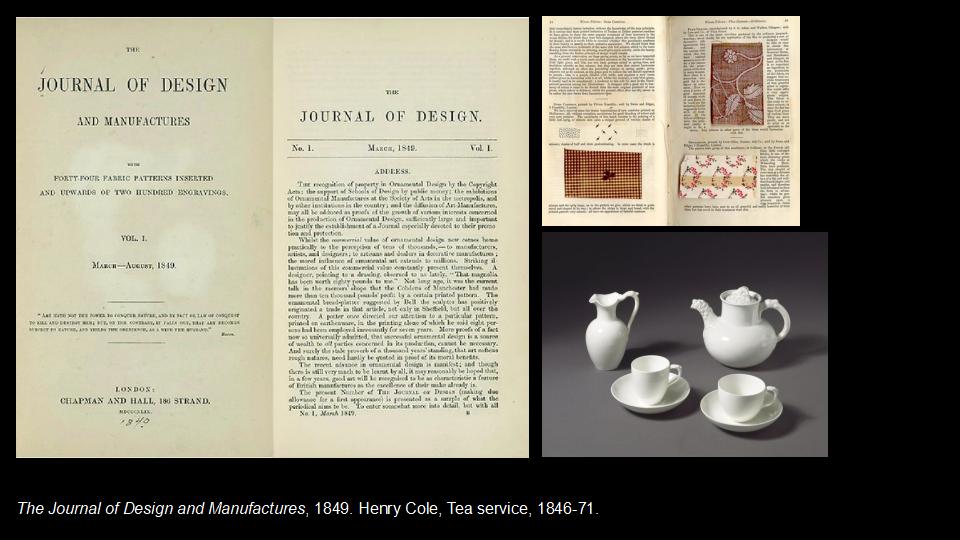

Inside this extraordinary building, which was later dismantled and rebuilt on another site, which you see here in a vintage photograph. The world of mass-produced objects was not to the level of creativity of the building itself. Very often, these objects were cheap mass-produced imitation of pre-industrial goods. So in short, there was a distance between the product exhibited in the building and what the building meant. This gap, this distance was the preoccupation for Henry Cole, who was the main promoter of the exhibition of 1851, and this gap prompted him already before the exhibition to engage in the publication of this periodical The Journal of Design and manufacturers.

The first publication devoted to the question of design with the idea of improving the quality of British goods to be exported. And clearly in this particular case, design was conceived in a close connection with the industries of Britain, called itself design China. As you see, but mostly the industrial branches, which were concerned, were first of all related to a textile industry, as you see on the top right. So London is the cradle of this new discipline —the discipline of design, which was practiced mostly by artists. One typical name that comes to mind is William Morris.

A second place, a second metropolis where we can find the roots of design is Berlin, the capital of United Germany. After 1871, the capital of the new German Reich, which was also a large center of industry and culture. In the country here, we see a view of Berlin before the Second World War, which at the height of its power and glory with its huge department stores and its factories. Berlin had been seen by the kings of Prussia around 1800 as Athens on the Spree (Spree is the river which crosses Berlin). For the industrial leaders of the early 20th century, one century later (later the modern was different), they saw Berlin as a possible Chicago on the Spree, a city also where industries, such advance industries like the electrical industries, were leading.

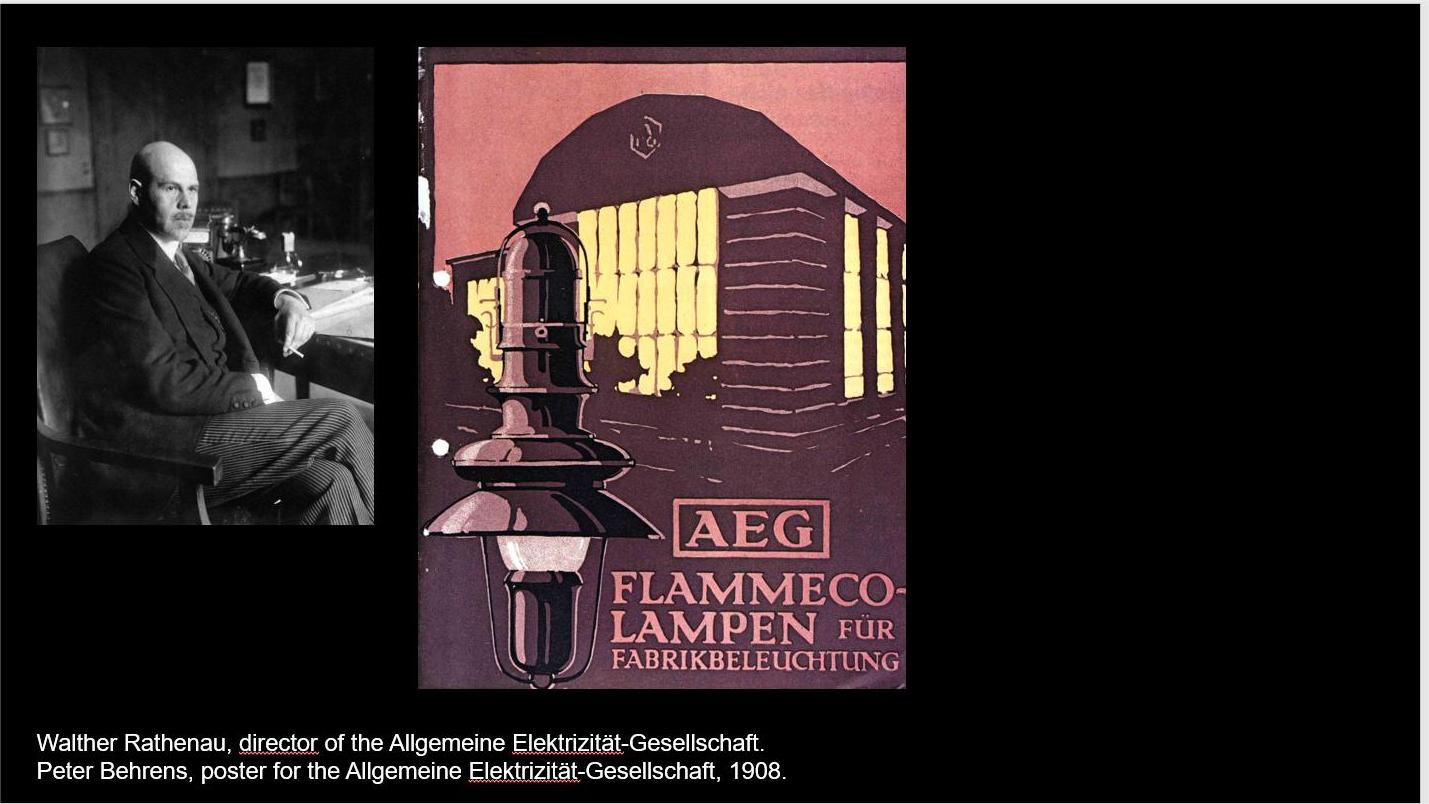

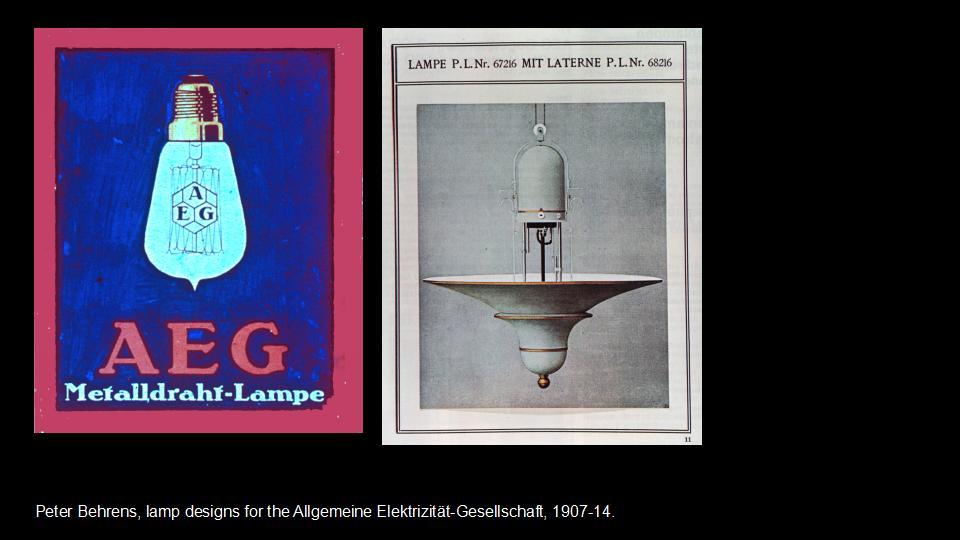

And here we see the major next step in the development of design, again as a concept, as a practice, as an ideology in German. The term used was Gestaltung (Gestalt is form, and this could be translated by “form-giving”). And the most important, single experience was one of the General Electricity company (AEG) lead on Walther Rathenau, a forward-thinking Industrialist and political leader who later became a minister of the weapon industry during the war. Rathenau engaged, whose father had founded the company, and engaged the painter Peter Behrens, who had already showed his skills as an architect to provide a comprehensive design service to the enterprise. So, Peter Behrens, as you see on the right, design the lamps, the products, but also the buildings. The wonderful Turbinenhalle, or turbine hall, for which drawings were made by the young Mies van der Rohe, a later hero of modern architecture in Germany and in the US.

Peter Behrens defined, managed a program of what we today called total design. Here we see on the left, for he even designs the interior wiring of this electrical bulb using the logo of the company. So he designed bulbs, but also the graphic design, selling posters, and the AEG type any design, many electrical appliances, which have not aged today. Basically kettles are fundamentally the same today. So the profile defined by Peter Behrens was the profile of the modern designer at the service of the entire production—to offer great form. The effort of Rathenau and his friends led to the creation of the Deutscher Werkbund of a German Union for the work, which aspired to put together industrial leaders, for instance here Karl-Ernst Osthaus, who was a textile manufacturer, and artist and architect such as Hermann Muthesius who had observed in England while being a diplomat in England, the development of British industry according to the lines defined by Cole. So the Werkbund brought to Germany the English experience and promoted an extraordinary quantity of good-quality designs used in all the realms of production from automobiles to ocean liners. And here I want to mention one interesting anecdote. Today, we tend to and I think it’s also true in China, we tend to see the logo “Made in Germany” as a sort of token of quality. At that time, the Werkbund reacted against the fact that the logo “made in Germany” had been forced upon the Germans by the British. At that time it meant cheap German imitation of high-quality British products. So what this effort of Werkbund and the subsequent German industries achieved was to turn around the meaning of the term “made in Germany.”

So, the next stage, and we remain in Germany, is of course the Bauhaus created in Weimar first and then Dessau by Walter Gropius. The Bauhaus as a building itself was a masterpiece of functionalist design. As you see the building was broken down into wings, which were each housing a particular function here. In the center, the most important one being the workshops. The studios where students worked at creating prototypes of products to be then taken over by industry. And this was the case for Marcel Breuer’s seats; this was the case for Wilhelm Wagenfeld’s silverware and lamp designs. So Bauhaus was clearly coming from the world of culture at the service of industry. It was also related, and I want to insist on this, Dessau is one hour away by train from Berlin, a little less today. So Dessau should be considered not as a city per se but as a satellite of Berlin, which remained the real center of institutional discussion on design.

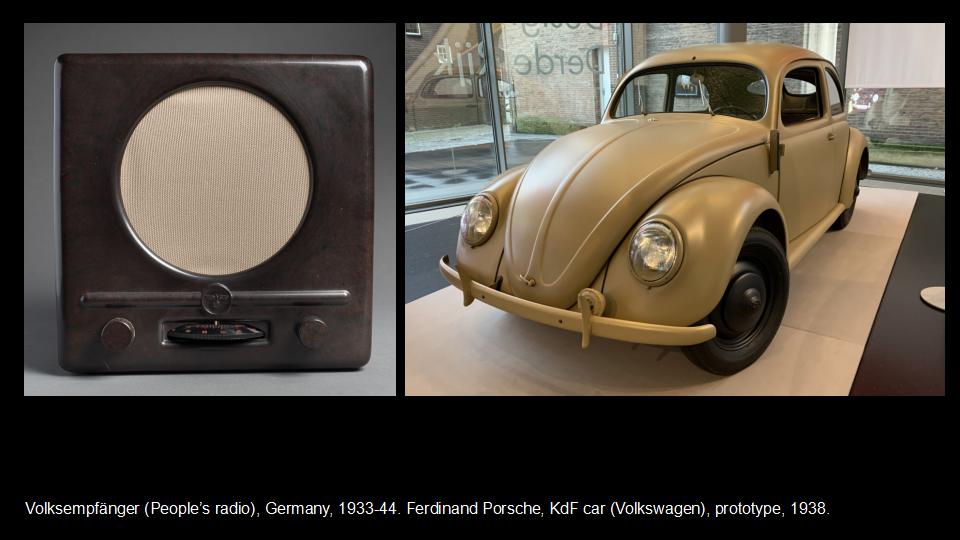

The work of the Bauhaus and the functional design continued to be developed during Nazis. And this is an interesting chapter, in which I can’t comment today. But how the Nazi Germany, as you know, are very strong and powerful totalitarian state. State used its design in order to produce, for instance the so-called people’s radio on the left and, of course, the Volkswagen on the right with which was born in a perspective related to the Fordism as industrial product, which would be affordable for the masses.

Let me jump above or across the world and stop in a third city, which became also a major capital of design, Milan, in northern Italy. Milan became in a certain way the world capital of design in the 50s and through the 70s. And here a parallel could be made with Shanghai, Milan is the second most important Italian city after Rome. Clearly the industrial capital and as I see in Milan's efforts to position itself at the forefront of design and industrial quality. I see a parallel with Shanghai. The second largest city in China, second most important, the city symbolically, which also has used and is using quality production and culture as a sort of mean of self-assertion.

So if we stick with Milan. Milan was great of a number of extremely interesting inventions in terms of design. Milan, and northern Italia at large, with Milan as a center. I would mention only some object, which you know very well, like the Moka espresso machine in a cast aluminum, which is an invention of the 1930s. Or the Piaggio Vespa Scooter, which was developed as the way to transform an airplane industry manufacturer into a producer of consumer goods. So this is something to be kept in mind: the Vespa was born because Piaggio could no longer produce warplanes after the Second World War.

There are something important to Milan and, I think, to design in general. The cities, big cities, metropolises are also places where a modern press was born, where intellectual life develops on printed paper and now of course through other media. And in the case of Milan, the relevance of design was really boosted by the existence of what we would call an intellectual conversation.

For instance, in the pages of the beautiful Journal, civilization of machines, or Civilta delle Macchine, led by the engineer Leonardo Sinisgalli, but where writers even poets like Giuseppe Ungaretti, Carlo-Emilio Gadda, Alberto Moravia, philosophers like Enzo Paci wrote essays, so here I think that one of the great privileges of the large cities of the metropolises is to put together people interested in technology, people practicing technology, and intellectuals. And this is where really creative reflection on what the object of modern life are. That's where this kind of reflection kindled up.

So in the case of Milan, very briefly, the objects produced by Milan’s very prosperous industry and conceived by two generations of designers. Some are well known, Franco Albini for instance, designed furniture using industrial finishes, but also the Milan subway which is a masterpiece of 1960s. Imagination, rigorous imagination.

I could also, of course, mention the role of Olivetti. Adriano Olivetti was not based in Milan. He was based in the small city of Ivrea, near, closer to Torino. But the designers who worked with him were Milanese, Marcello Nizzoli or Ettore Sottsass. They were, and, this is something really interesting, in the case of Italy, they had not been trained as designers. There was no such thing as a school of Design in Milan. They were trained as architects, but in a climate in which the everyday conversation between industrialists and intellectuals was intense. Olivetti himself was an intellectual. He was interested in the social senses in literature. He supported journals. He was active in political life. Yes, there is no secrets. The quality of the relevance and classicist of these designs was related to the long-term vision and the, I would say, comprehensive programs of industrialist like Olivetti.

Very important, also in the case of the expansion of design and sort of feedback effect on production itself is the public echo of designed objects beyond the professional milieu. And here I am just sticking to the Milanese situation. In 1972, New York became an outburst of Milan with the legendary exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art—“The New Domestic Landscape,” where the breath of Milanese, essentially Milanese production, was introduced to America and the world by the world's leading museum. And, by the way, MOMA has been the first Museum to include a department of architecture and Design in the early 1930s.

Here, we see two types of total environment, which were shown at MOMA in 1970, which show the preoccupation of designers such as Joe Colombo, Sottsass for an integration of the single and dispersed object, which usually constitute an interior.

Another in 1953 exactly. Exactly or more or less, 30 years after the creation of the Bauhaus, a new school was created in western Germany in a different context. It was no longer the context of Weimar Republic before Nazi. It is because the concept, the context of reconstruction of democracy in western Germany.

Max Bill designed this high school for design (Gestaltung, or form-giving, but design is also an apt translation), where the project of the Bauhaus was in a way resumed, revived with a clearly social intention, creating design, creating high-quality produced for the modern Postwar German industry—affordable products but quality products.

The epitome of this attitude is the work of someone like Dieter Rams and the products he designed for Braun. So this is related to the culture of the school in Ulm, which was closed for political reasons in 1968. Rams and his products for Braun are clearly the inspiration for a spectrum of products of designs. Which you know very well, which are the ones, which had been developed by Jonathan Ive for Apple for several decades until recently. Interestingly here. the connection of Ive with Steve Jobs, the founder and we said the wizard of Apple, has been fundamental. So again the couple between the designer and the maker and the industrialist is very important: it took place in a big metropolis, which is the greater San Francisco.

I will take one, I will go to, one last city, to conclude, Los Angeles, which is a gigantic metropolis and also one which wasn't known for its architecture, but in 1930s in the 50s and 60s, for its engagement in aerospace industries, in particular making of rockets and spaceships.

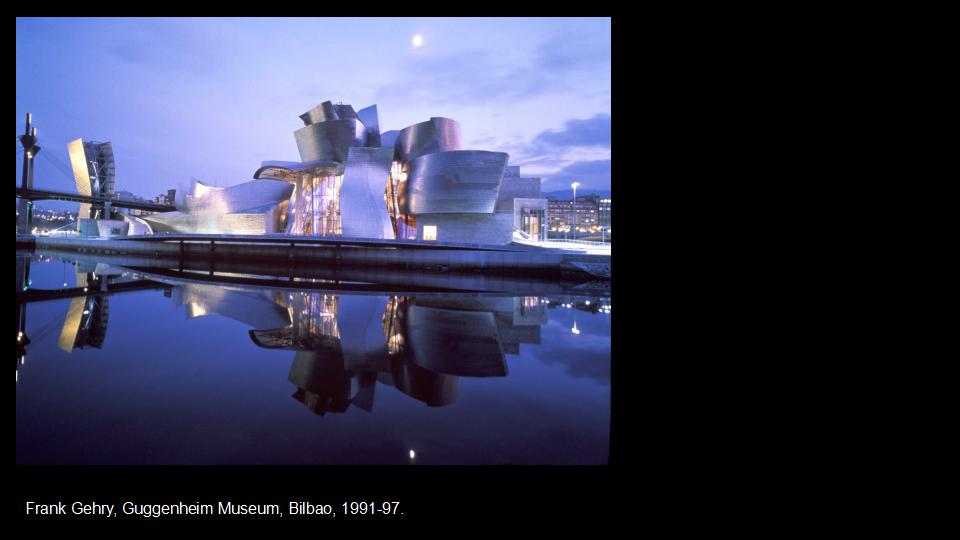

Los Angeles has been the home of Frank Gehry, one of the world's most interesting and provocative architects on which I’m producing for years a major, major comprehensive publication. Gehry's understanding of architecture is deeply rooted in the urban culture of Los Angeles. He says let him build great structures like the Guggenheim in Bilbao, but also to work on design.

There is a forgotten part of Gehry's work. Which is the combo furniture, which he developed in the 1970s and which failed because of him, because he didn't want to engage in commercial practices to make it to the greater market.

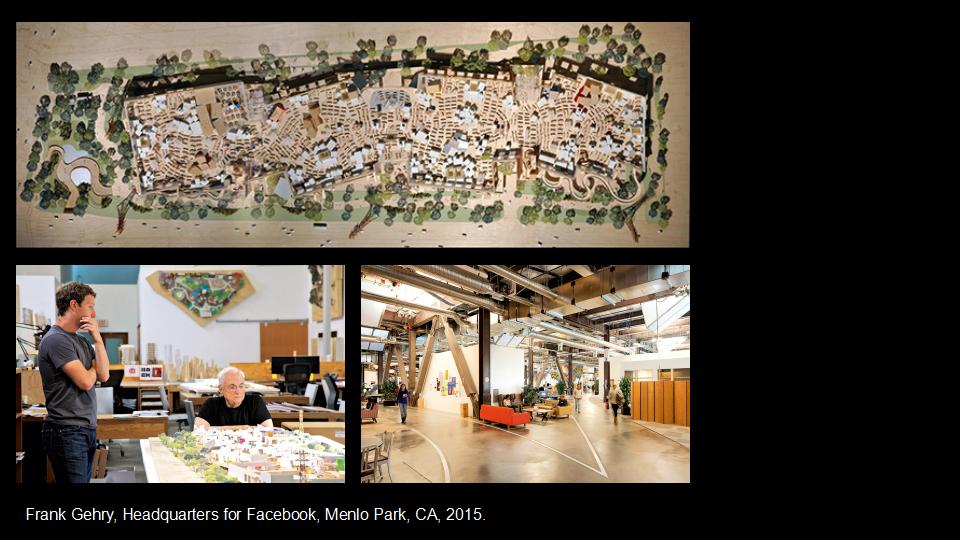

Interestingly, and this is almost my last image. Frank Gehry's office, more than Frank Gehry's creative practice, has become a model for other firms. And the best example is the large headquarters he built for Facebook a few years ago, which is modeled after the deployment of the designers in his own studio. So, here we see how architecture has provided is not only building structure used for creative businesses, which are on the forefront of the invention of software, of products, of lots of and lots of goods, material or immaterial. But we see also that architecture sometimes provides a model for their own spatial organization.

So what I want to say here, and this brings me back to a view you're familiar with. what I want to say is that in order for design to develop and flourish, design needs positive and favorable ecosystem. We've seen how this ecosystem was created in London, in Berlin, including the Bauhaus, highly developed in the great example of Milan. What is a creative and a positive ecosystem? In the case of these cities and also possibly in the case of Shanghai, I mean, it is as with the combination of many aspects we’ve seen: education, the production of knowledge, and the training of proper, of competent professionals. It’s the existence of visual culture and a sort of collective agreement on taste, which is promoted through publications and in particular through criticism. It is of course, and this is the underlying theme to everything we’ve seen today, it is also an issue, which is the one of intellectual property, of the rigorous protection of intellectual property behind all the product we've seen so far in this very brief lecture. There were patents, there were legal strategies to protect the creativity of their designers and their producers. So it is in this intermingling of intellectual activities, artistic activities, and the education towards them and industrial energy that design is born. Such an ecosystem is largely existing in Shanghai, need to be and it can be further developed. And I think here that the main thing is really the connection between the world of culture and the world of industry. This is where our contemporary world can bloom.

Thank you for your attention.