Xing Ruan:

“With External Change, Internal Consistency Persists”

The developing state of society with Chinese characteristics presents a unique environment for China's contemporary architecture. Furthermore, by serving as one of China's primary centers of design, Shanghai serves as an ideal entry point for understanding China's contemporary architecture. Architect Xing Ruan is the founding dean of the School of Design at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. Ruan left China for New Zealand and Australia in the early 1990s before returning in 2018 for his present post, giving him sharp insight into his role as scholar and practitioner situated in both East and West. In the following excerpts from a conversation between Xing Ruan and the author, Ruan talks about means of communication, perspectives on architectural history, humanism, and more.

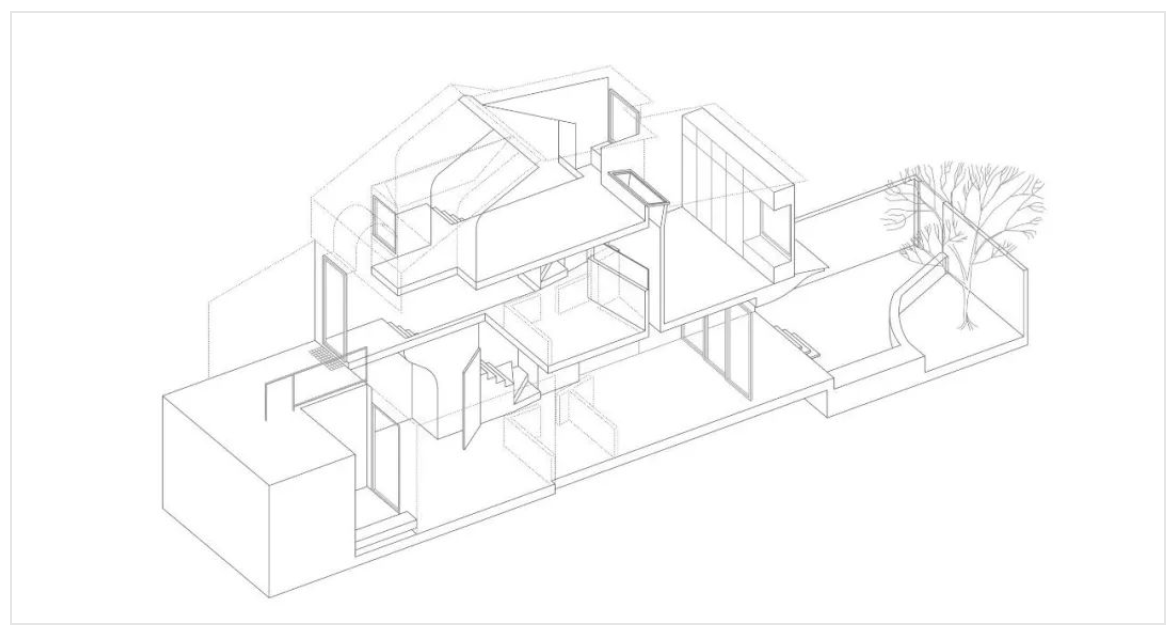

上海交大设计学院楼 / 阮昕 ©︎张益凡

上海交大设计学院楼 / 阮昕 ©︎张益凡

Here and Elsewhere

Yifan Zhang(YF): After you moved away from China in 1991, Chinese subjects were still a primary focus of your research. Similarly, it can be said that with participation in more projects abroad, many Chinese students and scholars still work on topics related to China.

Xing Ruan(XR): Many people tend to have a certain misunderstanding that if you are Chinese, and have grown up in this culture, then you certainly will understand Chinabetter than others. To speak frankly, the person whose understanding of Chinese culture I have the most respect for was a Belgian scholar who later lived for a long time in Australia. But why are there so few Chinese scholars researching other cultures? There must be some difficulties in doing so. The same predicament exists in the West, one related to the tendency for first impressions to remain deeply entrenched.

Last year, on a whim I went to give a lecture at the Politecnico di Milano (The Polytechnic University of Milan) on Palladio (“On Palladio: Common and Uncommon Observations from a Chinese Point of View”). In doing so, I shocked not only myself but also my Italian hosts. (Laughs) In the end, I was surprised. The lecture went down very well. Their attitude towards Palladio is like ours towards the Chinese courtyard—thinking what else can be said of it? This being the case, the tendency is to no longer consider the Palladio’s original meaning, nor its architectural essence.

佛斯卡利别墅远景 ©︎ 阮昕

Yifan Zhang(YF): That being the case when speaking of the sort of research that encompasses traditional vernacular buildings and Palladio, East and West, past and present, isn’t it the case that one cannot help but engaging in “comparisons”?

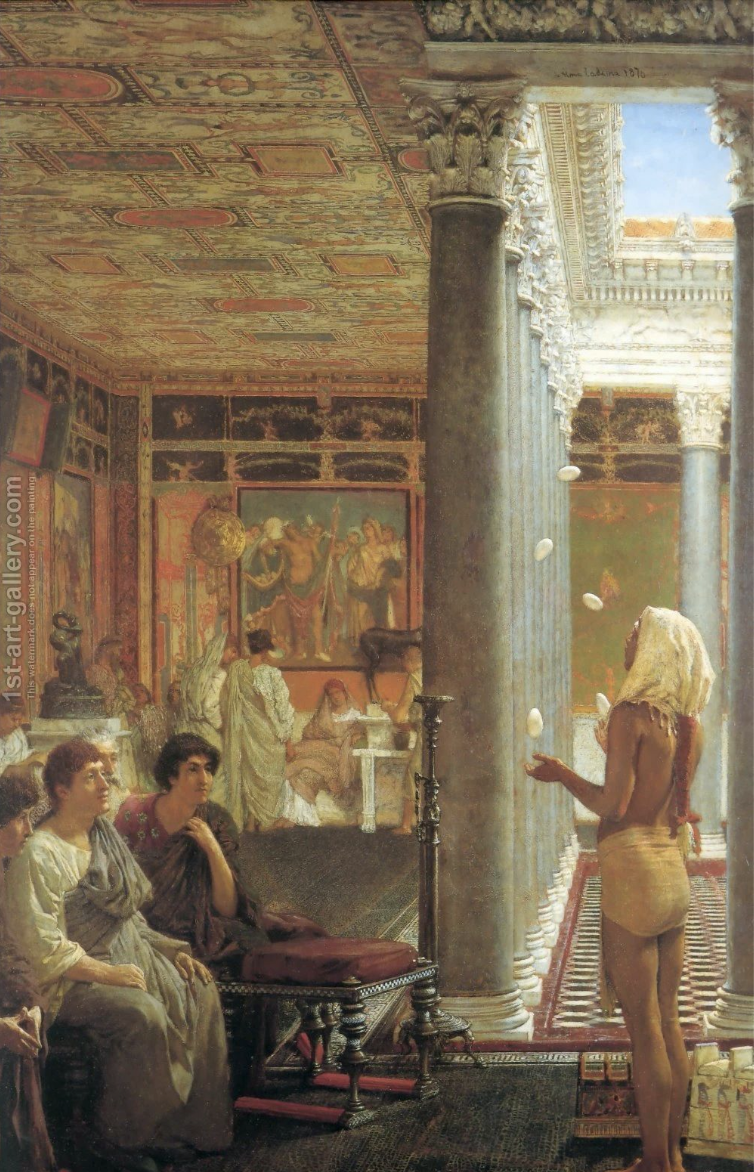

XR: When I left China, except for a few outstanding individuals, many of my generation growing up in the Cultural Revolution received a poor education. At the time, my Chinese cultural literacy was quite low, and my understanding of the West was also grossly insufficient. I think that this was quite common. I can’t say that before I went abroad I clearly grasped this, but soon after I did. Making comparisons really is not an academic matter but a question of personal curiosity, one that results in wanting to learn a bit more. Through gradual learning, one realizes that, to know the Western world, one must reach back to the ancient Mediterranean world, and Chinese civilization 2,500 years ago. And in that period, these two types of civilization had many similarities. It is very fascinating. Speaking of comparisons, I then naturally made comparisons between the Chinese courtyard and the Roman or Greek courtyards. It was very superficial, but I did it because I could not avoid doing so.

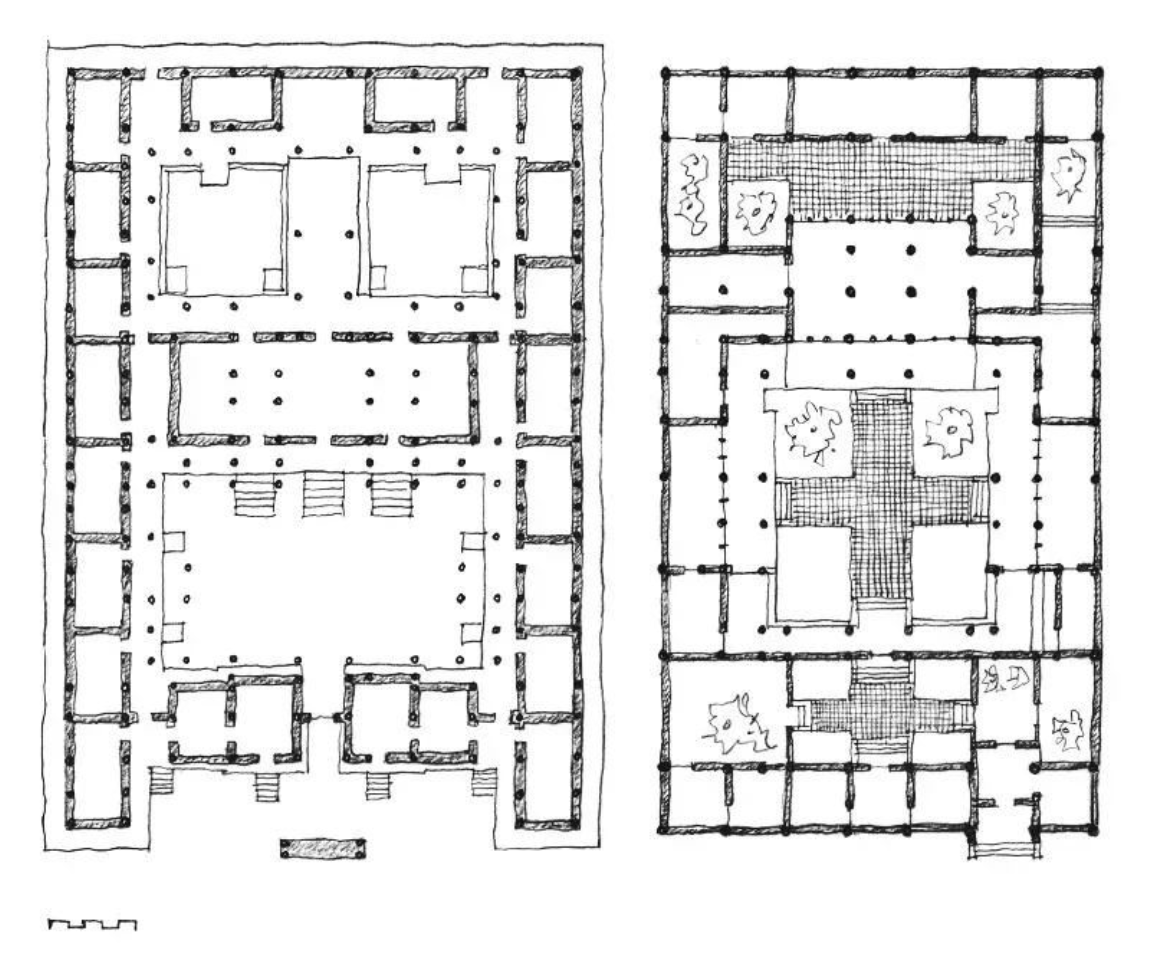

Ancient Roman courtyards and our Spring and Autumn Period courtyards have some subtle differences. Do these differences suggest the future divergent paths of Indo-European civilization from Chinese civilization? I think there definitely is a connection. Architecture thus has been a vehicle for life and humanity. Furthermore, what Chinese people call heaven, the West has called god. At first, this heaven and god were very similar, but they gradually diverged. In the West, there was a transition from a diverse culture of polytheism in ancient society to Christian society. Heaven became a god. Furthermore, god became more and more human-like, becoming the route of Western Christian culture. This is something not found in China at all. As Confucius remarked, “Of what words does heaven have? ... I prefer not to speak.” I specifically address this question in a book to be published in English at the start of next year.

凤雏西周合院(左)与明清四合院(右)

YF: Are your historical research and historical emphasis for the purpose of satisfying the emotional needs of nostalgia? Or is it to fill the void of the future?

XR: I think the two are inseparable. Generally speaking, we look down a bit at the longing for the golden ages of the past or the good times and view this as nostalgic and unrealistic. But I think this is a very beautiful thing. Because of the passing quality of time, nostalgia really is a very wonderful feeling. If one ignores this aesthetic sensibility, research will become a boring business. Based on this, anyone with a bit of truth-seeking spirit will incorporate the societies and eras of their own as part of a frame of reference whether intentionally or unintentionally. This is definitely the work of comparative research, producing the basis for our imagination and creations at present. As Joseph Rykwert writes in his beautifully crafted book On Adam's House in Paradise, the same can be said of our interest in the primitive hut. Only a very naive architect will call himself a genius, thinking that with one “masterful stroke”, he will prove his greatness, doing what others found impossible.

Also, the most important lesson of history is that humanity’s experience is finite. Experience can be accumulated in a certain area, but it will not be enriched indefinitely. To put it differently, our contemporary nature holds the belief that history has a developmental course. But if we admit to the limitations and restrictions of historical experience, history is seen not to have such a course. Hence it becomes the most important thing to be understood and studied.

Accuracy and Efficacy

YF: We previously touched on the concept of architecture as a vehicle, and on errors in communication. This made me think of the questions you raised in your 1989 essay about the use of architecture and language as a means for expressive communication.

XR: This does ring a bell (The sin of my youth!). At the time I possibly had browsed some material by Ludwig Wittgenstein, amounting to a simple starting point for a young man. Looking back on it now, there really turns out to be a certain continuity in a person’s intellectual trajectory.

YF: Since both express and communicate the ideas of a subject, is there possibly some interrelation between language and architecture?

XR: Actually, in the 1990s when I undertook fieldwork, the question was how many sorts of modes of expression were there for peoples without a written language who relied on oral traditions? The written language of the Han Culture is so powerful, far more than the culture’s physical objects. As a result, when compared with architecture, we focus more on the written language. So, for peoples within the context of a different written language, what sort of architectural culture will they have? One reason I was strongly moved by this question was because of postmodern trends at the time, supposing that by drawing a few symbols these questions could be resolved. It did not feel right to me. Is architecture that easy? Can such symbols really be understood by people? Through research on the Dong (Kam) people and on other peoples in southern China, I discovered that the transmission of architectural expression and significance does not occur by means of “reading” but is realized through the building process as well through ritual. People’s understanding of architecture is not simply a form of pure rational understanding but is interconnected with many corporeal experiences. I think this is an interesting topic. In fact it takes us back to the essence of architecture.

侗族村落,摄于1993 ©︎阮昕

Without exaggeration, the greatest creation of the Han Chinese culture is its language, and its supreme form of art is calligraphy—to which I’m afraid only Western classical music can be compared. Within this kind of culture which treasures language more than objects, either architecture’s ability to transmit information went astray or our ability to comprehend architecture got sidetracked. I guess it is the latter. If you examine so-called traditional Chinese architecture, you see a form of the courtyard (siheyuan) that has changed little in over 3000 years. While one doesn’t focus on the form, its significance cannot be ignored.

To sum it up, the power of the Chinese written language has influenced how we think about architecture. Obliviousness leads to distortions. After composing so-called classical architectural symbols in the 1980s, which were then worked into form making, at present we are running out of tricks. What form is there now that has not been tried?

YF: Do you mean language, despite being inherently imprecise, being a powerful means of communication suppresses architecture’s own expression and symbolism? And that architecture is in fact a more accurate form of communication than language?

XR: It is not to say that architecture’s accuracy exceeds that of the written language, but that its efficacy is stronger and has more force than language. To express and understand a certain meaning is not a matter of accuracy. Like what Pierre Bourdieu, a French anthropologist and sociologist, described, it seems like we modern people think we have strong self-awareness, that we know what we are talking about. But this is not entirely true. A person occupies a position somewhere between that of a calculating game player and a mechanical puppet. People cannot achieve a complete understanding of consciousness and cannot realize real self-awareness. I think this is a philosophical question and a question about humanity. However, a big mistake made by our modern mortals is the idea that we are saved, that we have artificial intelligence, big data, and that we can clearly calculate, hence understand anything. This is wrong! Even I do not really know who I am, and I do not completely know what I am doing.

This is the biggest misconception in the social sciences, the application of methods for studying objects to researching human consciousness. From the perspective of philosophy and human consciousness, this cannot result in accurate results. If we say the architecture has a strong efficacy in conveying human consciousness and emotions, this refers to the various forms of resonance and dialogue produced by man and objects, man and place, and man and space. Because of this, it is very compelling, but it is not a question of accuracy. If you went to interview an ancient Roman who had attended a ceremony for the founding of the city and asked him in Q&A format according to our present framework of thinking, this would represent a misconception about people and humanity.

YF: Is that to say there is no way to know the truth or the real situation?

XR: You certainly should not know everything. If you knew the truth about human consciousness and emotion, life would not be worth living. There would be no sense of mystery, and no need for artists, or architects. An architect who does not view himself as an artist is making a very big mistake. Even worse would be to see himself as a designer of forms, in which case there is no hope.

阮昕策展2019上海城市空间艺术 季规划建筑板块 ©︎苏圣亮

YF: “Of that which one cannot speak, one must remain silent.” But art can be compelling in its expression. Doesn’t the art of architecture rely on its physicality of form to a certain extent?

XR: I think there is a misguided trend in which architects act as designers of symbols, and then turn symbols into forms. From symbols in the postmodern period to speaking of form-making at present, or tectonics, it feels a bit like we are coming to the end of the rope. That we only need to know what building material requires of us, and then let it lead us by the nose, making us feel some sort of noble brilliance of craftmanship—is this not a joke? Can you let an object lead you by the nose? The character of an object, if there is any, it must have been endowed by man. For instance, if you say a mountain is beautiful, but then look at human history, you see that the meanings of landscapes change. There is nothing that can be divorced of its relationship with people.

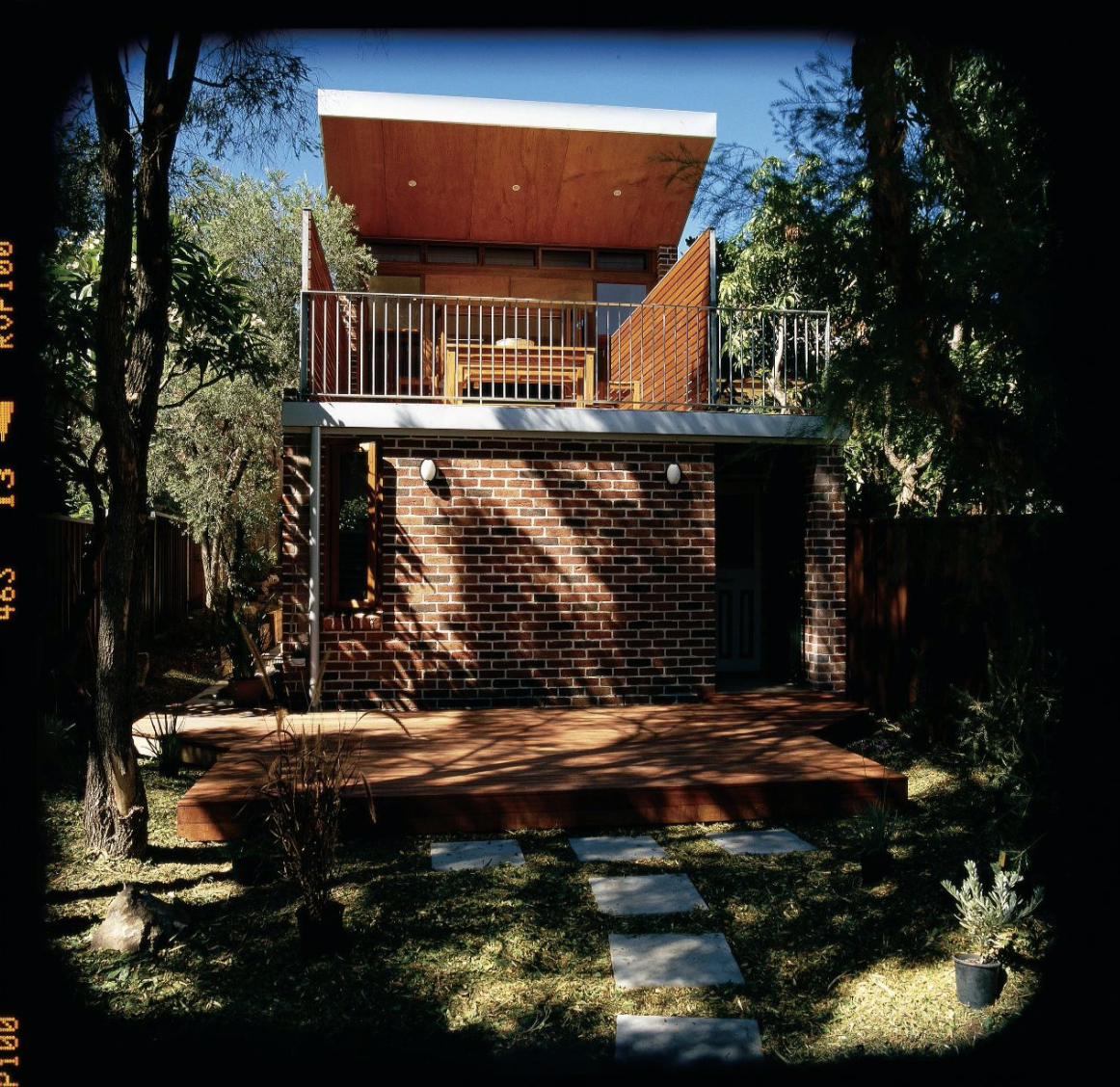

悉尼阮宅,建筑师:赵东敏、 阮昕 ©︎ 阮昕

Segregation and Boundaries

YF: Considering your emphasis on the importance of history, and your somewhat mysterious description of humanity, it is hard for me not to speculate about your attitude towards modernity—the destruction of superstition, conquering the vast, or the “disenchantment” spoken of by Max Weber. The emphasis on interior space in your projects in Sydney seems to express this idea.

XR: We have simplified and formulized the concept of modernity, especially in the field of architecture. I think so-called modernity and pre-modernity exist both in ancient times and at present. This is because I have confidence that there are certain consistencies in mankind. Meanwhile, in architecture, we easily attribute the notion of modernity to certain present technological achievements. Thus, it seems to represent a comparison between open, permeable, and flexible buildings on one hand, and the enclosed, inward tending structures of the past on the other.

悉尼阮宅,建筑师:赵东敏、 阮昕 ©︎ 阮昕

But the development of modernity in the West is in fact a process tending towards inwardness. Based on the foundational awakening of self-awareness, partitioning was the symbol of modernity in the 19th century. Together with the help of the segregation of architectural interiors and the partitioning of cities based on metrics, a well-organized healthy modern society was formed. Is this not the trademark of the Victorian era? This is different from the present understanding of modernity that is based on architectural form. We are presently facing just this problem. The world has changed overnight because of COVID-19. When can the situation be restored? Will our conception of modernity be transformed from one of openness and mobility back to one of segregation and control? Time will tell.

悉尼刘易斯宅,建筑师:赵东敏、阮昕 ©︎ 赵东敏

We will be confused if we use representational forms to define modernity and non-modernity. Regarding the question of internal versus external, we should not see the problem as a relationship of form, as this would likely lead us to deviate from the relationship to people. Instead, I think it is greatly preferable to view the internal versus external as a question concerning people.

悉尼莱富史通宅,建筑师:赵东敏、阮昕 ©︎ Eric Sierins

YF: Does this refer to "interior life”?

XR: This term expresses a concept from the West. Only the West will describe the so-called interior, interior life, or the interior landscape of the mind. This is all Western language. The danger is that it is very easy for us to formalize and objectify the notion.

In Chinese language, for instance, in the novel Dream of the Red Chamber, is there any expression like that? Certainly not. If we must use the words of the West, then what was the interior life of traditional Chinese people? A Chinese pavilion is open to all sides. If you stand in the pavilion, and the pavilion is situated amidst mountains and water, besides the Western Lake, then you are in a situation in which the outside changes but the inside ought to remain consistent. A traditional Chinese courtyard is enclosed, but the space for imagination there is without limit. Such is Chinese culture. On the other hand, the West must rely on physical form.

Editor's Note: This article was translated by Yifan Zhang and Abraham Zamcheck.