From Explorer to Pioneer:

Martha Schwartz’s Philosophy of Design Education, Practice and Research

On November 20th and 21st, 2019, the first International Symposium on the Idea of Design Education was held at the School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU). Over 100 eminent educators, scholars and practitioners from world renowned universities and colleges in China and abroad were invited. They are leaders from landscape architecture, architecture, urban planning and design backgrounds. The symposium was intended to discuss how design education can cope with the grand challenges facing humanity today, including related ethical and technical issues. Professor Martha Schwartz, who was invited as a keynote speaker, was interviewed by Ms. MO Fei(School of Design, SJTU) during the event. A comprehensive discussion on her philosophy of design education, practice and research was carried out at SJTU.

Q1: Professor Schwartz, it’s my honor to discuss landscape design and education with you at Shanghai Jiao Tong University. After reviewing students’ work at SJTU, what do you think are the main strengths of landscape design teaching here?

Martha: It is my great honor to be invited to be here, and to have the opportunity to interact with students at SJTU. I was impressed by the amount of knowledge the students have so they can assess environmental and social issues and problems on sites. They have a very holistic comprehension of what is happening about climate change and even suggest including community involvement. They are very well equipped with a huge variety of different ideas and practices and demonstrated solutions that create systems, or “virtuous cycles” of benefits.

Q2: What do you think is the best way to teach design? Could you share some core teaching philosophy?

Martha: My fundamental teaching philosophy is to help students to understand themselves, to find their own design language through which they can express themselves. Above all, I do not to teach students what I do, or to think what I think. I teach to help each student to discover what they feel and what they have, as an individual, something inside of themselves to offer others. These are the most important things I can do to teach design. I believe this is also the key to cultivate creativity.

After having 28 years teaching design, I have come to recognize that we must have designers and/or artists to teach design. Design cannot be taught through someone without enough experience designing and making things. Creation is a personal endeavor; it comes from within an individual and therefore our processes for creation are all different. But artists and designers can teach others to design, using their own perspective and experience. A one-size-fits-all curriculum or teacher does not exist in good art/design school. As an example, at the GSD there are many designers in the faculty, and we have designers from around the world to teach studios every year. A great variety of ideas, methods, aesthetics and philosophies are offered to the students. It is up to the student to find their own directions and ideas. Design education must teach students how to think freely and critically.

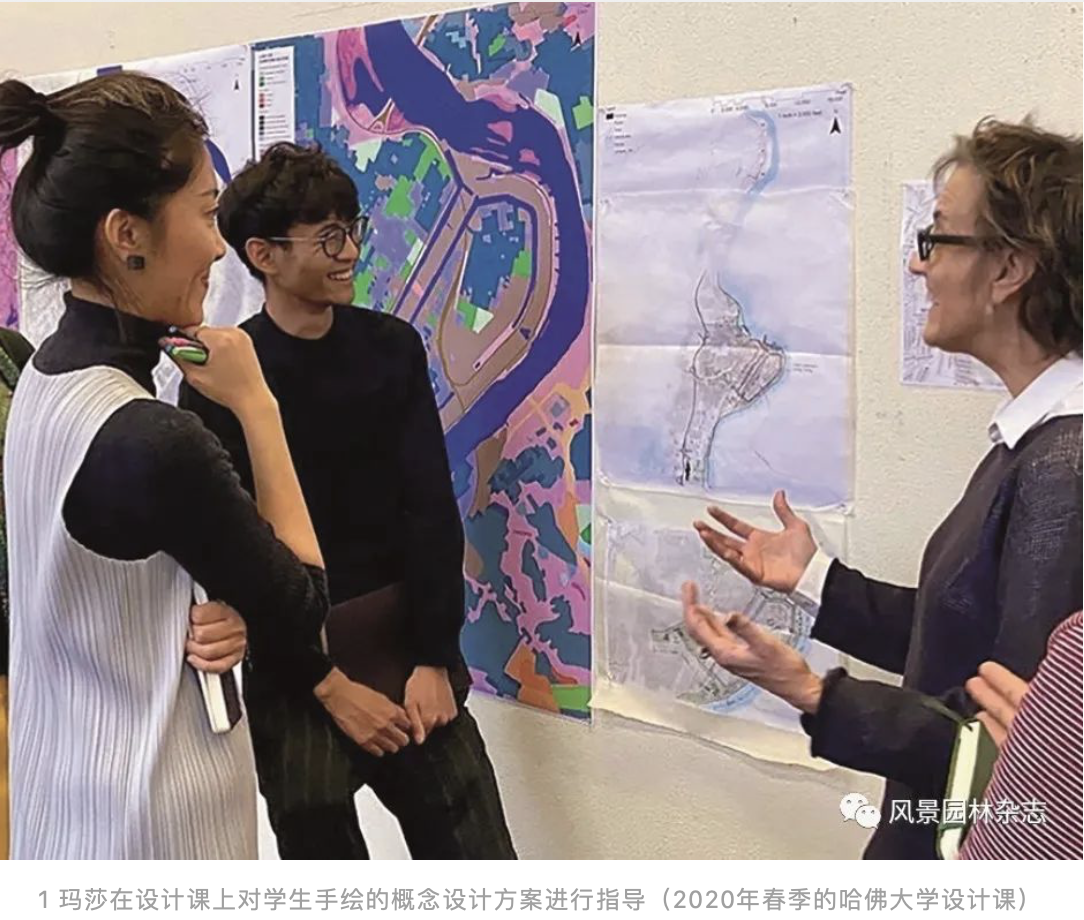

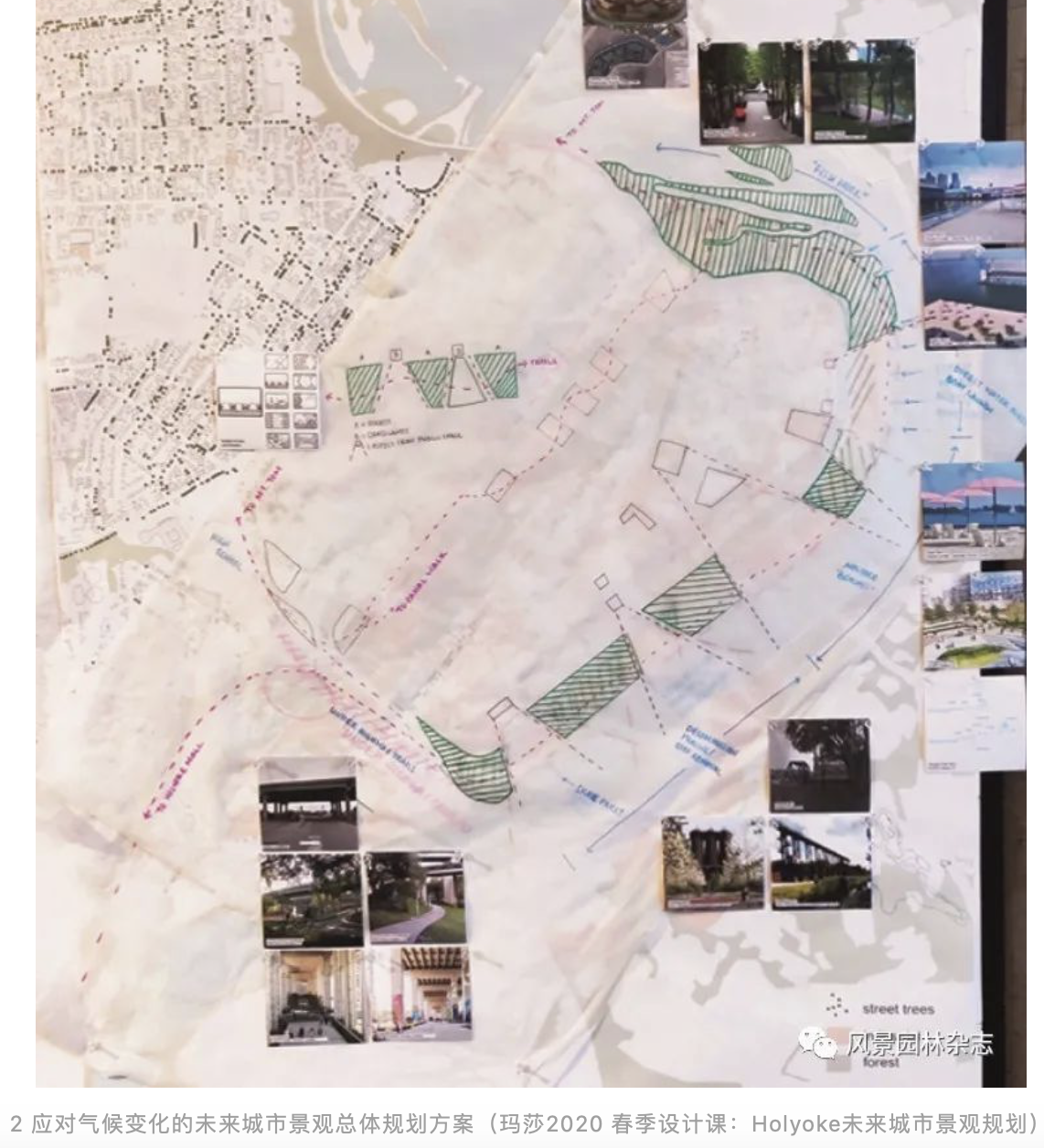

I believe we cannot use computer to teach people how to design; drawing by hand is required to generate design ideas in my studios (Fig. 1, 2) and practice (Fig. 3). The reason is simple, the computer is not a device for teaching creativity. Parametric design uses algorithms, a program that takes a form (one idea) to produce hundreds of variations of. However, the original idea that is put into the computer is only one. In this sense, it is a “vertical” exploration of one idea, and limits “horizontal” thinking, meaning there are less ideas that are generated eventually. Sketching ideas are visual thinking, making form while observing, thinking, evaluating, revising and shaping all happen at the same time. The design process goes more smoothly, quicker, with a better sense of scale. New ideas can be generated easily. The only way to cultivate non- linear intuitive thinking is through the coordination between hands and eyes.

We must raise awareness of the value of intuition, and enhance relevant training to open students up to its potential, if teaching design is an objective. Intuition (or “non-linear logic”) is like a chaotic spider’s web, making many more random connections than in ‘linear logic’ that allows the creative process to generate new ideas (Fig. 4). I am an “intuitive” person, meaning, I take in a lot of information, perhaps unconsciously,and then, internally, without using linear analysis, I am attracted (or not) to something - a piece of sculpture, an idea, a tree in a forest, or maybe a person. If I am attracted, I then become more analytic and linear, to understand why and what qualities about what I am seeing has attracted me. But my very first response was to let my intuitive brain find what I was curious or interested in. It is essential, for designers and artists, to have this “portal” into ones’ brain so the information that results in an “intuition” can lead you to understand who you are. And understanding who you are (what you like, don’t like, are attracted to etc.) is essential to any successful artist or designer.

Lastly, one cannot be a complete designer if not interested in art. Artists are the “researchers” of the visual realm. Artists often start with studying existing forms of art, explore it, and then expand or reinterpret it. This means that they wish to test a new idea or aesthetic that has not existed yet. In order to do this, artists are very inquisitive, challenge the status quo, and break into doing and thinking in another way. This is why artists are often viewed as “radical”, because they are challenging what most people consider “normal”, or “traditional”. They are interested in what is “normal” only to challenge it through exploring new ways of seeing, thinking, and making. That are what artists do. It is why they are so important to cultural and societal evolution. Our education should not only cultivate students’ taste of art, but also to encourage them to think freely and critically like artists, full of curiosity and courage.

Q3: At SJTU, we have students from very diverse backgrounds. Some of them studied art before entering university, but many others do not have relevant experience. What is the situation at GSD?

Martha: We experience similar situations in the GSD where people come from all different backgrounds, which is a very good thing. The real challenge is how to help students to overcome the “FEAR OF DESIGN”. This is the most common barrier but cannot be overcome easily. People who come into design at a later stage in their education are usually very hesitant to expose themselves because they are afraid of failing. Our students at the GSD are not used to failing. This hesitation to work with one’s hands and make shapes is a very large mountain to get the students over.

Making mistakes is a good thing! It is our job as design teachers to allow students to make mistakes, and encourage them to try things, fail and try again perseveringly. If this is done, students will be able to start to design better without the “FEAR OF DESIGN”. Making mistakes is part of the process, which only hand-drawing can provide, as it is easy to recognize something you do not like as you are drawing, and draw over it until you get it “right”. This is a process of learning.

In addition, sufficient time for basic trainings is essential to equip students to adapt design curriculum. Students should be trained to see, to build art foundations, to make models by hands and to think in three dimensions critically, so as to slowly build enough confidence to start exploring on their own.

Q4: As you have mentioned that developing self-awareness is crucial, may I ask if you have any particular suggestions on how to do this? It seems not easy to understand our preference and gifts in design.

Martha: It is not easy. The most basic thing of design is to learn how to “see”. What kind of things you are attracted to? What allows you to see? What does texture mean? How do we react to colors and space? If you draw, how would you really interpret the light bouncing on this table or water? These are all things everybody sees but we are not thinking about it. I would like to take people on a trip to see art and I will ask them to pick something they really like. We do experiments, a little kind of design in a box, and learn how to interpret it. It is really sensing and getting to understand why I like this, why I feel it is important and how we can express it in forms. Through this process, to help others to trust intuitions, to understand and express themselves. Sometimes people are very hesitating to expose themselves because they might be criticized. It’s really up to you to decide whether you like it or not, not others.

Q5: With regards to landscape design, what is your fundamental design philosophy?

Martha: There are many aspects of design I will have thought about. Fundamentally, design is a creative act. Yes, we solve problems, but design must go beyond problem solving. It is not enough to “solve the problem”. As designers, we give shape to what needs to be done. Through design, we make the last, and perhaps most important step, which is to make an emotional connection to people. Evoking an emotional response from people can bring another level of experience to people, such as the creation of a memory, a sense of wonder or curiosity, and pleasure that is felt when we experience something of beauty.

Q6: Do you have any favorite personal built work, such as one that represents your key design philosophy?

Martha: I really cannot rank my own work, as it is like choosing among your children who is the best, which is not possible. But the works that remain strongest in my mind are the ones I built with others. These were art installations, and are still my favorite because I have so many memories attached to them. The Bagel Garden is still vivid in my mind. It is both a tether and a great piece of luck at the same time and that is why it is so special.

Q7: Could you tell us a bit more about the Bagel Garden, as it is so special?

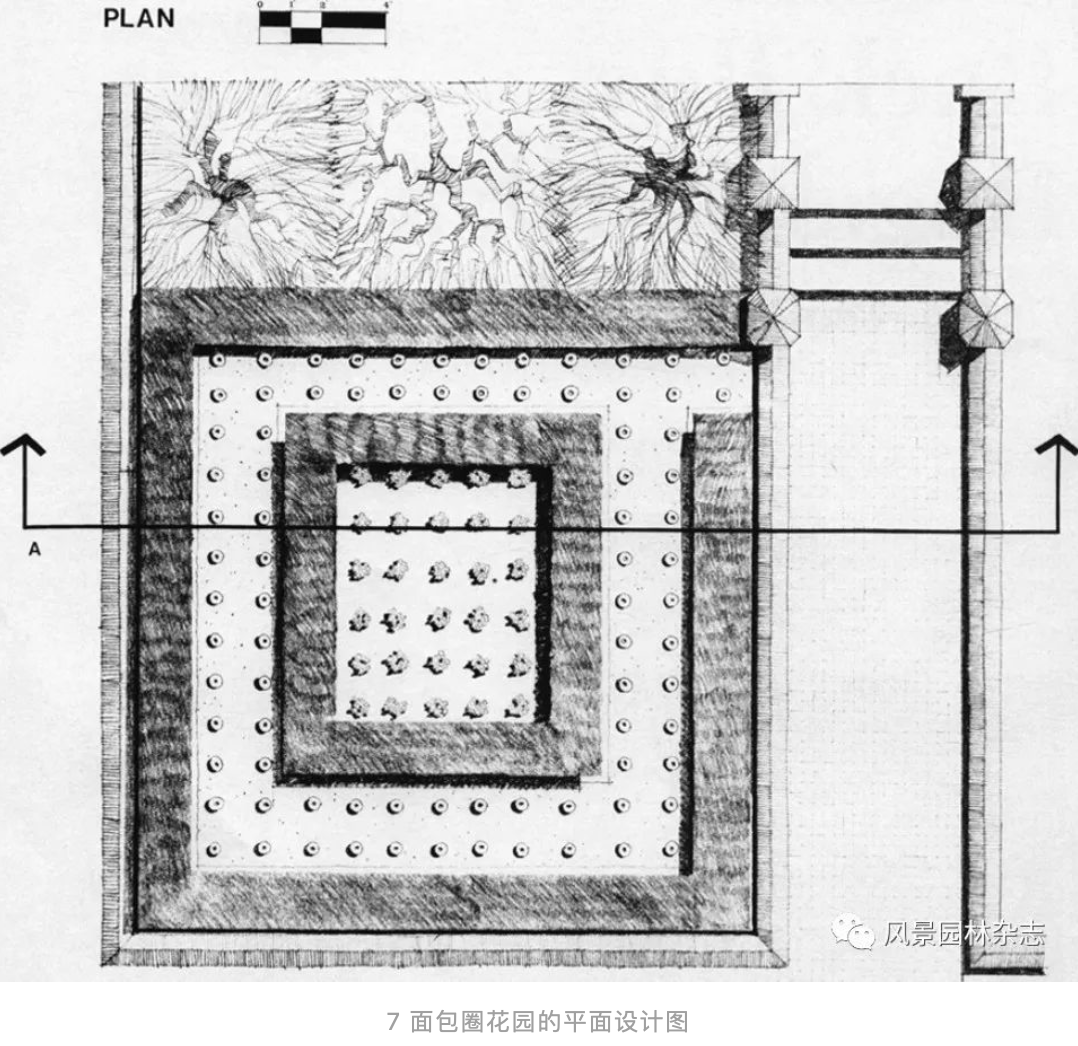

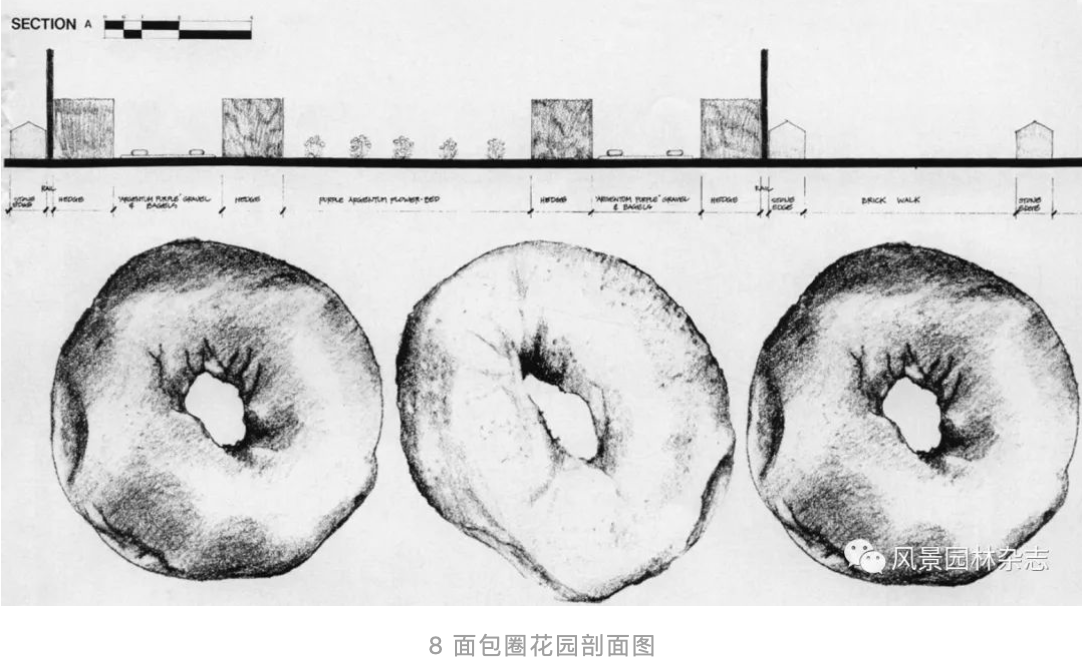

Martha: The Bagel Garden came from a very humble beginning. I did it as a funny joke and a ‘surprise party’ for my husband when he returned from a business trip. I had built this funny garden in front of our house in Backbay, Boston using bagels (Fig. 5). Friends encouraged me to send a picture to the Landscape Architecture Magazine, the official publication of the American Society of Landscape Architects. The editor of the magazine, Grady Clay①, responded, saying he would like to publish this, but I must write WHY I had done the Bagel Garden.

At that time, I was quite critical of the landscape profession. I had a strong background and knowledge of the artworld, landscape design was using very a specific design language and style that was very ‘modernist’. I was very frustrated by the trend that chasing good materials and fine details.

In my article introducing the Bagel Garden, I argued that the bagel was an “appropriate landscape material”, as it is inexpensive (far less costly than plant materials), available (from the corner deli), easy to maintain (requiring no watering or weeding), require no sun (which is essential to this north facing garden). In fact, this was making sense out of nonsense, but a more significant opinion was expressed in the next paragraph:

“There is presently a wealth of new ideas in materials and spatial arrangement which can be translated from the art world into landscape. From a social perspective, the increasing costs of our traditional palette of landscape materials and construction methods has placed our services well beyond the financial reach of people who could most benefit from our talent (particularly those live in depressed urban areas). However, we must remember that design is not intrinsic in materials, it is the relationship of forms in space.”

The photo of Bagel Garden was published on the front cover of the Landscape Architecture Magazine in January, 1980 (Fig. 6), and my article that introduced its design was also published in the same issue (Fig. 7, 8). As it is the official publication of ASLA, the publication of this work brought huge controversy at the time. In May of the year, the magazine published readers’ comments in an article entitled The Bagel Garden: Clear and Loud, which included diverse opinions. This revealed the publication directly impinged professional opinions of landscape design. Some people commented that it is too ugly! But a lot of people said other things, which is like maybe that is interesting, or maybe we could see that in a different way.

6 面包圈花园刊于美国

Landscape Architecture Magazine 1980 年第1 期封面,由美国 Landscape Architecture Magazine 授权重印

The debates commenced from how we and the landscape could start to come together. Why landscape cannot have a content? Why it cannot be conceptual? Why we cannot have a debate about it? Why it cannot be futuristic? Why does it always have to be appropriate? So that is how the transformation started from, but it was also because of the braveness of Grady Clay and the Landscape Architecture Magazine.

Q8: How can one cover photo bring about such remarkable influences?

Martha: How can one idea change the world? How can one painting change the world? How can one book change the world? This happens because it does. That is why. That’s why what we do and why we think things are important. You can change the world as an individual. Karl Marx, Picasso, these are all people who come up with ideas. It is a risky business not to do the same thing as everybody else. You always pay for that. It’s always difficult. Grady is a hero. If he didn’t do that, I’m not sure the profession would be where it is.

Q9: Thanks for sharing with us the hidden story of the Bagel Garden. Could you list a few more personal favorite designs from a designer’s perspective?

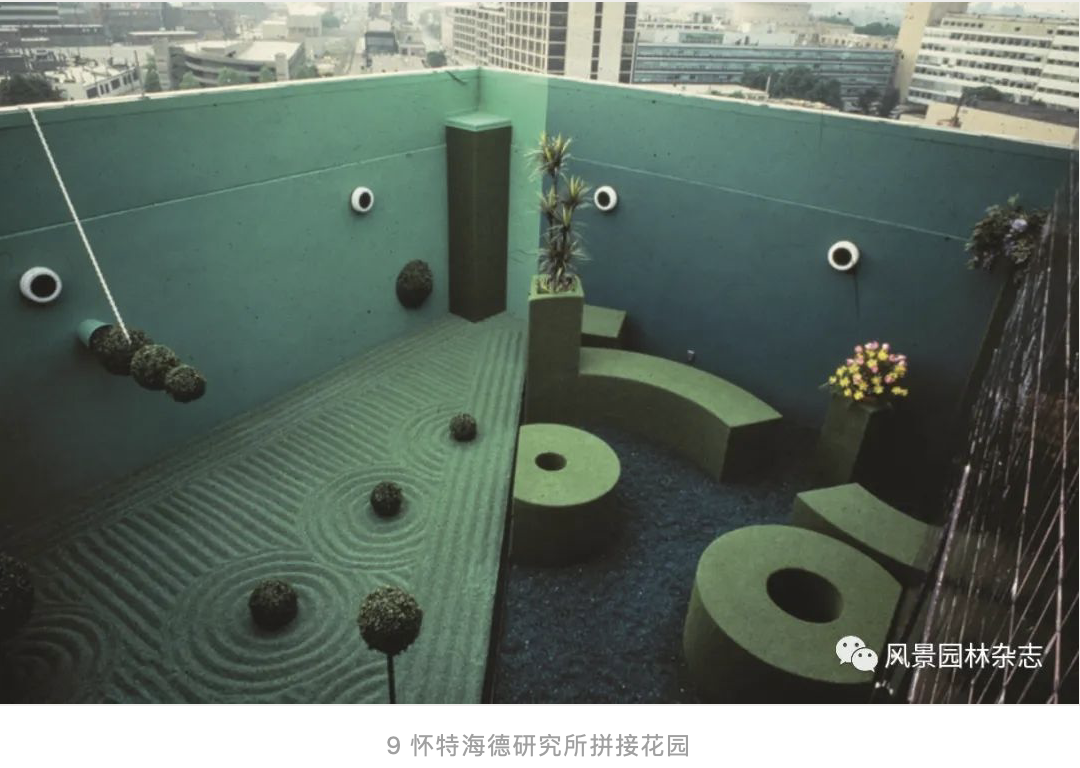

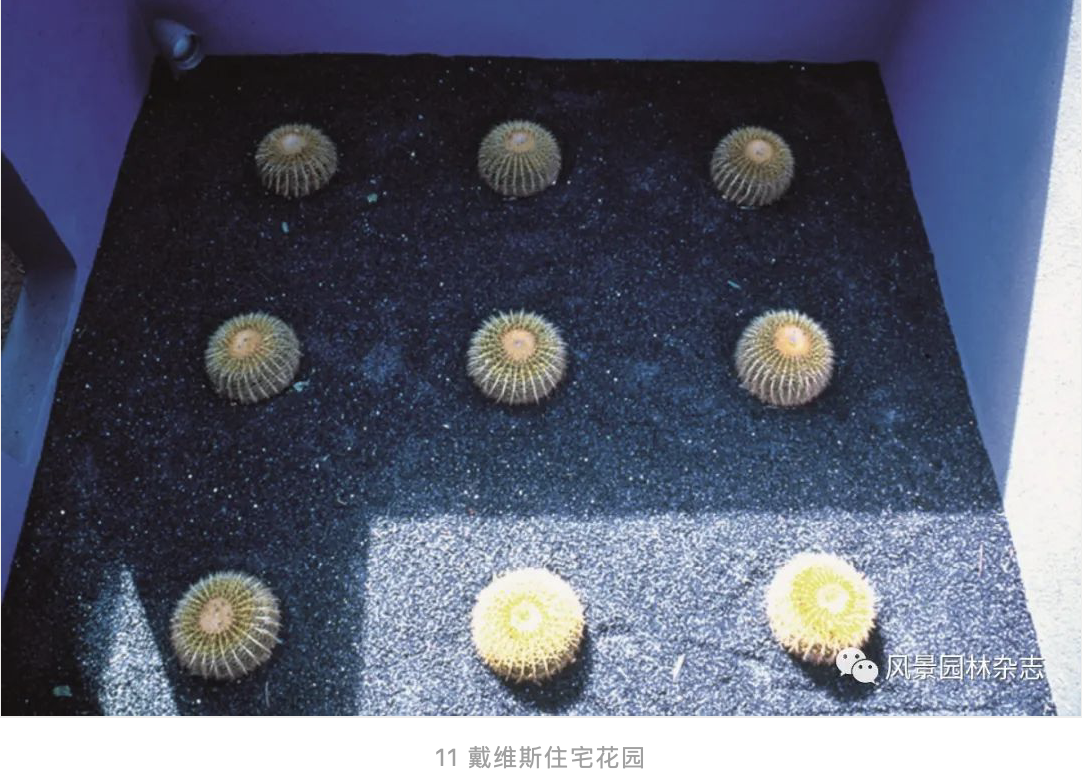

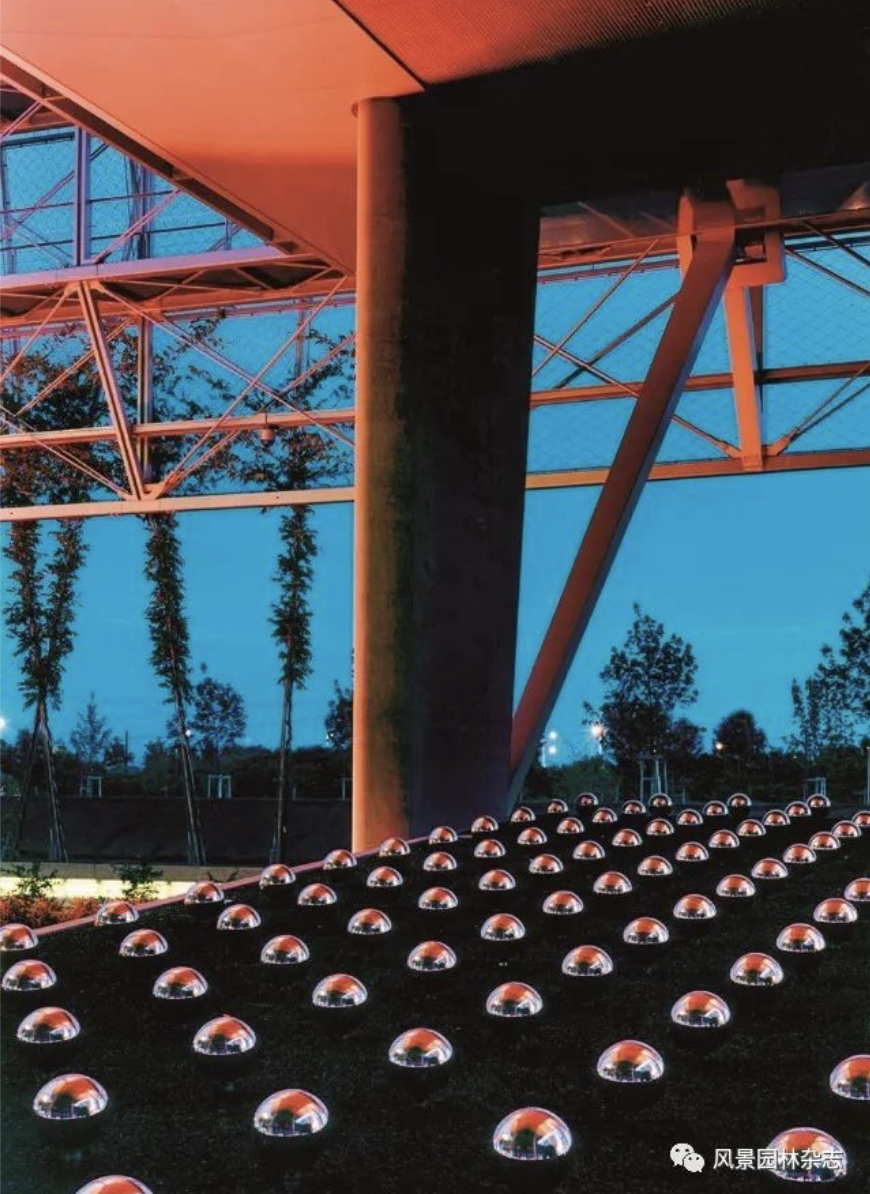

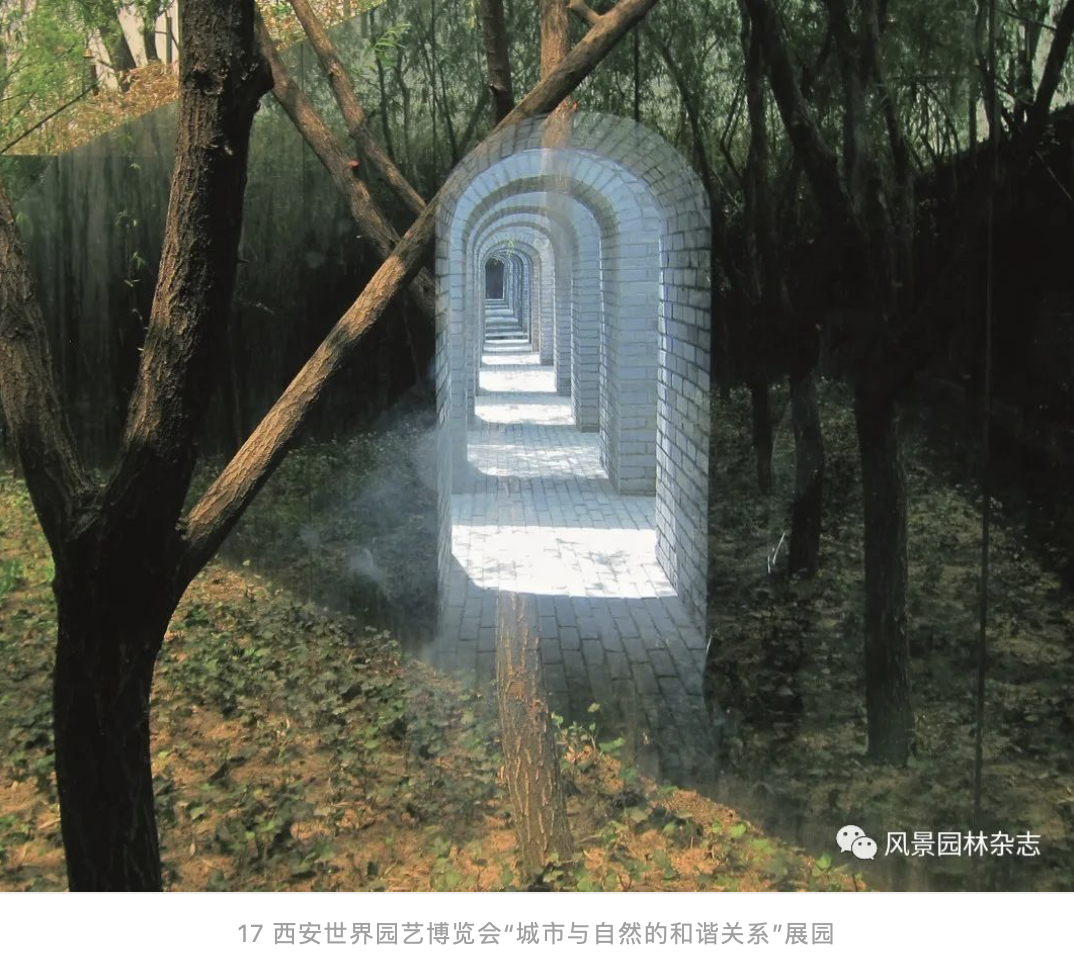

Martha: My favorites include some small art installations, with a few larger projects, such as Whitehead Institute Splice Garden (Fig. 9), Miami Sound Wall, Spoleto Festival Tribute to Slave Women (Fig. 10), Davis Residence Garden (Fig. 11), Swiss Re Headquarter Garden (Fig. 12), Mesa Arts Centre(Fig. 13), IBA Power Lines (Fig. 14), City of Tomorrow - Malmo Willow (Fig. 15), 51 Garden Ornaments (Fig. 16), Aluminati - Reykjavik Museum of contemporary Art, Xi’an International Horticultural Exposition “The Harmonious Relationship Between City and Nature” (Fig. 17) and Chongqing Hot Pot Garden (Fig. 18). There are some favorites that never got built. That list is too long!

12 瑞士再保险公司总部花园

Q10: As an outstanding designer, educator and artist, how can you balance different roles?

Martha: I am not sure if I am successful at all my roles, at any one time. I am a mother, wife, have a practice which is very demanding, I teach, and am building a non-profit organization to fight climate change. Maintaining my family is the most important role. I have three children. I believe trying to balance work and family is the biggest challenge of all. I would guess that most women who are working feel the same.

I have been very lucky to have my own practice, and I have been able to live/work at the same place. This is an ideal situation for women with kids. But most women do not have this privilege. If I had had to leave my children when they were so young, I may have chosen to stay at home. All along the way, I have to make choices about things. I’ve made lots of choices and decisions about where I am, what I will do or give up one for something else. But in terms of teaching, I find teaching is a lot more valuable right now. Previously I really just want to build and make things, but now I’m keener to thinking about things.

We lose a lot of women in the field of landscape architecture after having children because the job is rigorous and demanding so they choose to be with their children, which I completely understand. But the way we construct our workplace, hours of work, whether we can establish more flexible working rules and to promote policy that can support women and children, will affect many people’s life choices. It is up to us to make changes.

Q11: In your opinion, what is the role of landscape research for future environmental development?

Martha: There is so much research we can do. I focus on urban area because 70% of human populations are living in cities until 2050. There are so many issues that we need to resolve in cities. Urban heat island effect makes it so people, especially poor people, can’t stay in their buildings. People are starting to go out into the streets and green spaces. So how do we capture the water? How do we recycle? How do we integrate different systems? If we could somehow integrate design engineering into our ideas, we could learn how to build technologies that can help us to improve ecological services.

Decarbonization will be a direction that is full of potentiality. The world’s soil, forests, grasslands, wetlands and peatlands draw down 25% of all the carbon in the atmosphere. This is the core of our profession. Learning about new ideas, practices, technologies will be essential if we are to lead in decarbonization, which will be a trillion-dollar economy that is just starting now. While architects and builders put CO2 into the atmosphere, landscape architects will know methods of how to decarbonize. This is what we must learn about.

These are all things that need to be researched. But if we think our only task is design, we are trapped by only have a little knowledge. The more we understand our world, the more imaginations can invent things. So, we are stopping ourselves from becoming creative without understanding more. Our departments have to start joining with engineering and earth sciences departments. We have to have a much bigger understanding of not just ecology but the earth system which is beyond the scale of ecology. Given we are facing the effects of climate change globally, I believe we should and can step up to the next scale of engagement- which is the understanding of global systems (the EARTH SYSTEM). We have bump up to a much bigger scale of understanding and action. We must go from the scale of ecological-scale-thinking (local/regional-scale) to earth-system scale thinking (global scale).

Acknowledgments:

Particular thanks are given to the Department of Landscape Architecture, Shanghai Jiao Tong School of Design, and Martha Schwartz Partner New York and Shanghai Offices.

Chinese Version Proofreaders: Professor WANG Yun, the Head of the Department of Landscape Architecture, SJTU; LI Qingyun, undergraduate student, SJTU.

English Version Proofreaders: Professor Martha Schwarts, GSD, Harvard University; Kimberly Tryba, the Head of Business Development, MSP; Abraham Zamcheck, Ph. D. candidate, SJTU.

Interview Transcription Developers: LI Qingyun, DU Liujun, WU Zhequn.

Photographers: TANG Feilong, WU Weiwen, Huang Jishu, WU Jiong. (The names mentioned above are undergraduate students at SJTU).

Note:

① Grady Clay, known as Fearless Grady Clay, working editor of the Landscape Architecture Magazinefrom 1960 to 1984. https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2013/03/20/grady-clay/.

Sources of Figures:

The image of the interview was photographed by WU Weiwen and was amended by HUANG Jishu. Fig 1, 5, 9-18 were provided by MSP New York Office; Fig 2 was provided by CHEN Haina, a postgraduate student at GSD, Harvard University; Fig. 3 was provided by MSP Shanghai Office; Fig. 4 was photographed by MO Fei; Fig. 6-8 were originally published by Landscape Architecture Magazine in January 1980. Copy rights and reprinting permissions were obtained from the sources that provided the Figures.